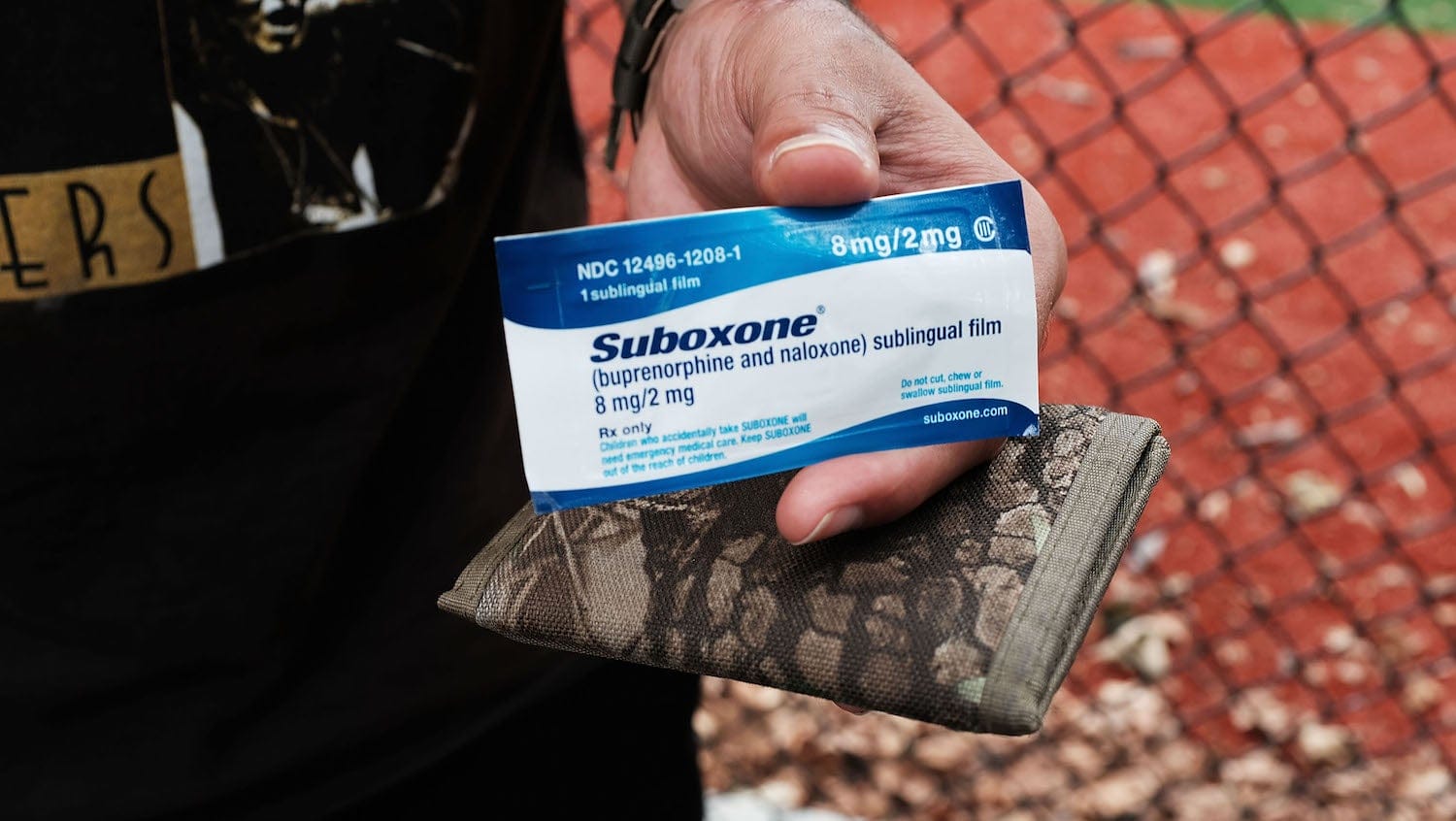

Getty Images

Although the opioid crisis has grown into a systemic problem, a systems-level response has been fatefully slow to materialize.

Several significant obstacles contribute to the struggle to treat opioid use disorder (OUD): the lack of access to effective medications, a shortage of inpatient beds, and the continued criminalization of opioid use. Compounding all of these challenges is the lack of coordination across the corresponding domains by the people and policymakers who oversee them. Although the opioid crisis has grown into a systemic problem, a systems-level response for treatments for opioid addiction has been fatefully slow to materialize.

This is the thinking that gave rise to Project RESPOND, a five-year research project funded by the National Institute on Drug Abuse that seeks to accelerate our understanding of the OUD treatments that work — and, more importantly, translate those insights into policy changes.

Led by Benjamin Linas, MD, an infectious diseases physician with the Grayken Center for Addiction at Boston Medical Center and an associate professor of medicine and public health at Boston University, Project RESPOND combines sophisticated simulation modeling and the Massachusetts Public Health Data Warehouse, a first-of-its-kind initiative that brings together 22 opioid-related datasets from numerous state agencies to probe open policy questions ranging from the availability of outpatient medications to treatment for opioid addiction in correctional settings.

A multidisciplinary team of clinicians, epidemiologists, health economists, mathematicians, and software developers is now putting the finishing touches on the simulation model. HealthCity sat down with Linas to hear more about RESPOND and what we can expect from the output.

HealthCity: What are the biggest gaps that you see in the treatment for opioid use disorder today?

Ben Linas: We’re in the middle of a crisis. People are dying. And there are effective opioid addiction treatments — buprenorphine, naltrexone, methadone — that are available and FDA-approved. They’re not perfect, but they decrease mortality and prevent people from actively using drugs. And yet, if you look at the data, fewer than 1 in 4 people who have an OUD are on those medications.

There’s a debate in the addiction world about the value of outpatient medications versus inpatient residential treatment, but even inpatient treatment is underutilized.

It’s hard to come up with another example of an illness for which treatment is there, but for some reason no one wants to use it. Fifty percent of the people with OUD are in no contact with any part of the system at all. That’s a system that’s not working.

HC: What sparked the idea for Project RESPOND?

BL: The project began when the Massachusetts Department of Public Health (DPH) came to us in 2017 with a very specific question: How many beds do we need to build? They’d made an insight that if people stay longer in a detox facility, they do better. So, they wanted to figure out how many new treatment beds to build, to help people stay longer. And that’s actually a common response.

We started meeting with them and thinking through the problem. And together we realized that how many beds we need is probably not the right question. The question is really about how to decrease overdoses and how to adjust the system, including treatment beds, but also outpatient capacity, emergency departments, detox — the entire platform that right now is not working together.

It really started hand in hand with DPH, which we’re proud of, because that kind of research directly with stakeholders and policymakers is ultimately what we’re about. That can change policy. That’s where the real work is happening.

The problem’s gotten too big. It’s a systems-level problem and it needs a systems-level intervention.

HC: Where does the simulation modeling come in?

BL: Simulation models are a tool. They let you construct a simulation of current reality and then play with alternative realities, where you can do different things and observe what might happen without having to actually spend money or impact people’s lives.

We’re building a simulation model of the population of people who have OUD in Massachusetts. The goal of the simulation is to accurately reflect the experience and outcomes of people with OUD in terms of things like overdoses, fatal overdoses, admissions to hospitals, treatment-seeking behaviors, and utilization of therapies. Once we’re confident that the natural history model is working well, we will layer on treatments, and we can start experimenting.

The simulation will ultimately project both the outcomes and the costs of interventions, so that we can make estimates like, “If you start doing buprenorphine in emergency departments in Massachusetts, this is how many overdoses it will prevent, and it’s going to cost X million dollars over the next three years.”

HC: How do you go about constructing the model?

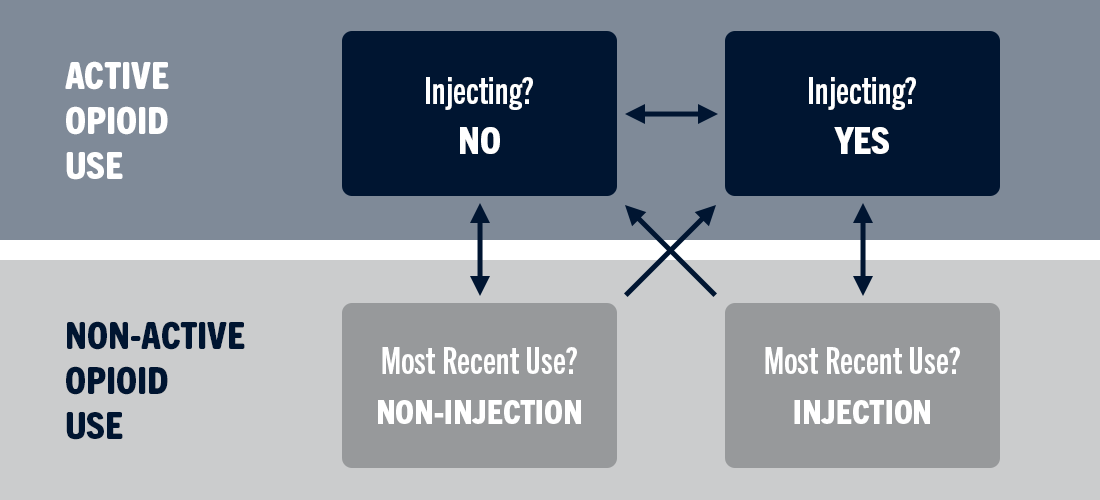

BL: This simulation is at the population level and represents a series of movements or transitions between different health states. At the core, there are four opioid-use-related health states: actively using opioids versus not actively using — and among those who are actively using opioids, they can be injecting opioids or using opioids without injection. Once the model has people in the right spot, it can start thinking about things like the risk of overdose or other complications based on current drug use.

The four core states at the heart of the RESPOND simulation model.

The second level that sits on top of the simulation of drug use is the transition into treatments. The model can represent things like going to detox, transitioning to outpatient buprenorphine or methadone or naltrexone, getting incarcerated, and entering inpatient residential facilities.

HC: And the idea is, when you deliver the insights of the simulation models to policymakers, they can use them to make the case for specific policy changes?

BL: Yes, hopefully. That translation step is critically important and often overlooked. We actually are part of the Center for Health Economics of Treatment Interventions for Substance Use Disorder, HCV, and HIV (CHERISH), a NIDA-funded health economics Center of Excellence that explicitly focuses on that last step you just mentioned. The classic thing is to say, “Look, data!” And then everyone says, “Great, thanks” — and they do whatever. And it’s frustrating to the scientists, because it’s so clear what the policymakers should have done.

So we actually think a lot about how to translate these mathematical simulation models — which, you know, can be a little bit opaque — into actionable messages for policymakers, to make sure we’re giving them what they need to make decisions. If you come in with, “Look at this amazing fancy simulation I did,” and then present the data the way you would at a methodological conference, you can see the lights go out and no one pays attention.

HC: Is Massachusetts ahead of other states in creating the Public Health Data Warehouse, and the level of coordination it represents?

BL: We’re definitely out in front. Other states — I can’t list them now, because it’s moving so quickly — are trying to do similar things in linking datasets, but to my knowledge, at this point, none of them is anywhere near as extensive. And none of them, that I’ve seen, is generating public data reports yet.

HC: Does Project RESPOND ultimately aspire to influence OUD policy nationally?

BL: There is a national OUD problem, but it’s really 50 state-level problems that combine into a national problem. We chose very consciously to make a state-level simulation because there isn’t really a national intervention. There’s national decision-making around budgeting and where we’re going to prioritize, but it’s the states that actually implement things. Where the rubber hits the road and where the policies are really made is at the state level, and that’s why we made a state-level solution.

But once the Project RESPOND model starts working for Massachusetts, we’d like to do it again for other states, using their data, so they can make their own appropriate state-level policies and choices. There’s not really a one-size-fits-all blanket for the problem, and that’s why we’re working to create a customizable model.

HC: Partnerships are central to the RESPOND approach. Has a lack of partnerships limited our ability to treat opioid use disorder to date?

BL: I do think one thing that’s been holding us back from making progress is divided, siloed thinking. It’s going to take a team intervention approach — we call it team science — and it’s going to involve multidisciplinary strategies. You can’t just say, “My detox does this, but we don’t have a relationship with the jail, and we don’t actually have a direct relationship with the hospital across the street.” That’s just not going to cut it. The problem’s gotten too big. It’s a systems-level problem and it needs a systems-level intervention.

This interview has been edited and condensed.