The Creator of a Viral Black Fetus Medical Illustration Blends Art and Activism

January 13, 2022

By David Limm

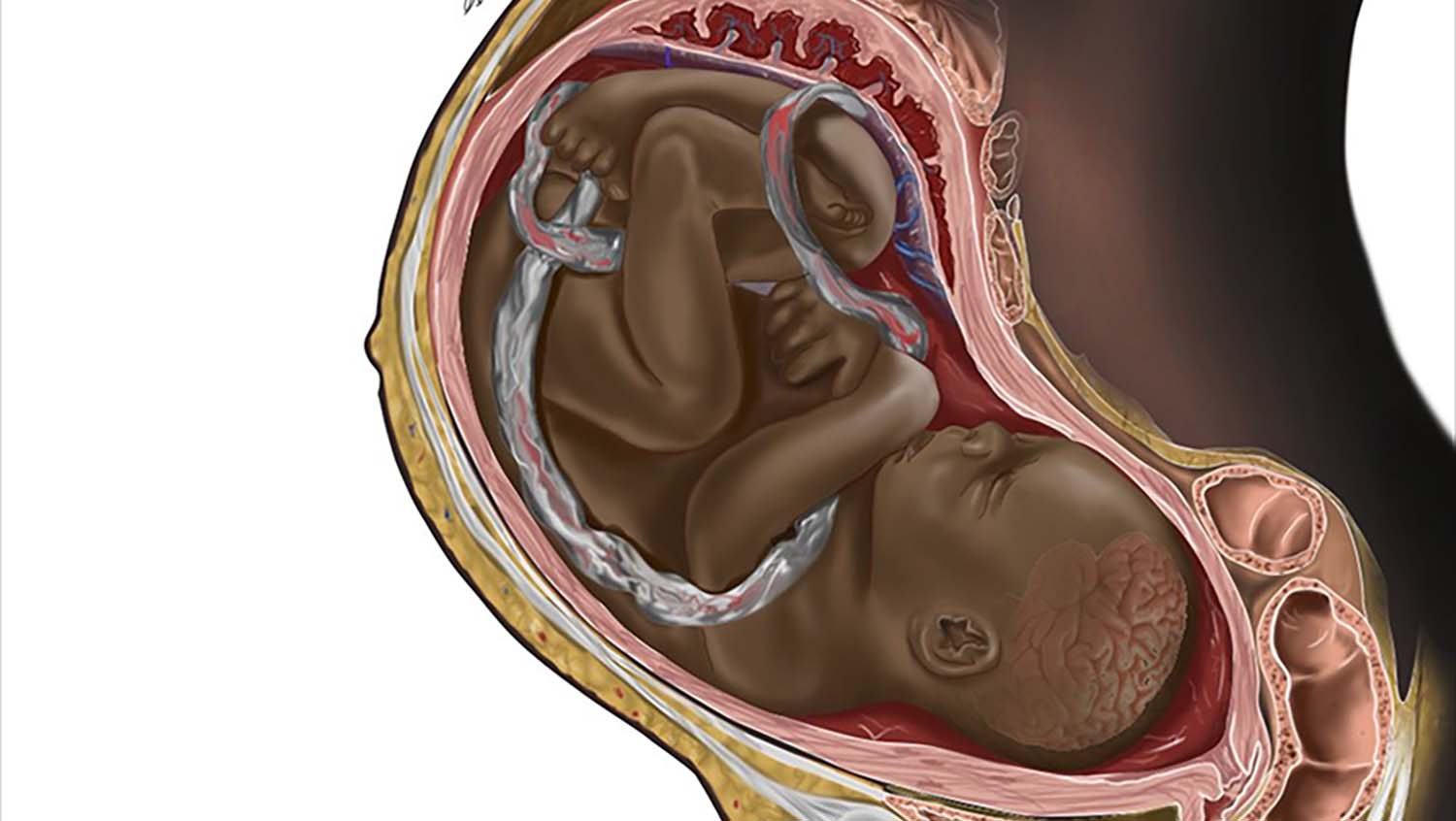

Courtesy of Chidiebere Ibe

Chidiebere Ibe says his work is not just about the lack of representation in medical illustrations. It's also about the beauty of African culture.

As an aspiring medical illustrator, Chidiebere Ibe noticed the absence as soon as he began to learn the craft. Why aren’t there more images of Black skin in medical illustration?

In a healthcare system beset with racial inequities, the relative scarcity of dark skin tones in medical textbooks is no exception. Driven to correct this imbalance, the Nigerian-born would-be neurosurgeon started teaching himself to illustrate, using Black skin to depict various medical conditions and procedures.

One-and-a-half years and one viral illustration later, Ibe is now a student at Kyiv Medical University in Ukraine, a budding illustrator, and an advocate for racial health justice. Over the past few weeks, his image of a Black pregnant person and fetus struck an instant chord on social media. For many, the picture was a reminder that racial bias can permeate every level of healthcare and medical training.

“I’ve literally never seen a black foetus illustrated, ever,” said one Twitter user, whose post with the image helped propel the illustration to virality. “Seeing more textbooks like this would make me want to become medical student,” said a commenter on Ibe’s Instagram post.

Ni-ka Ford, a medical illustrator whose work is a favorite of Ibe’s, said on Twitter, “Bias towards able-bodied whiteness in medical education materials is very harmful, it contributes to inequality and disparities in healthcare.”

Tejumola Adegoke, MD, MPH, an OBGYN at Boston Medical Center, the department’s director for Equity & Inclusion, and a leader spearheading equity in pregnancy initiatives for BMC’s Health Equity Accelerator notes that representation of Black and Brown people in medical education and illustration is “long overdue.”

“We may see pictures of dark skin in representations of sexually transmitted infections, but rarely in visual depictions of normal physiology,” Adegoke tells HealthCity. “Even manifestations of common cardiac and dermatologic disorders are rarely shown on people of color; it is not hard to imagine how this lack impacts medical providers’ ability to recognize and manage these conditions accurately for anyone is not white, or how much more challenging it is then for someone of color trying to assess if a change they have noticed warrants medical attention.”

The OBGYN added that she hopes to see images like Ibe’s, and from other medical illustrators and educators who prioritize inclusion, become the norm.

“People from minoritized racial/ethnic groups have waited far too long to see themselves depicted positively in the healthcare system,” she says.

A 2018 study of four anatomy textbooks frequently assigned at medical schools found that dark skin tones were greatly underrepresented, making up less than 5% of more than 4,000 images analyzed. The same study also found that, despite having higher mortality rates for six common types of cancer—breast, cervical, colon, lung, prostate, and skin—Black people appeared in fewer than a quarter of images depicting cancer. None of the cancer-specific images showed what the study deemed to be dark skin tones.

Race matters, and skin tone matters in medicine, especially in dermatology. Research has shown that when dermatologists fail to recognize disease in Brown or Black skin, the results can be deadly.

“The medical community needs to wake up and start fixing the way we recruit, train, and equip clinicians to reverse the trend of Black Americans dying too early and too often,” wrote Art Papier, a dermatologist who studies diagnostic errors in medical decision-making, in STAT.

HealthCity spoke with Ibe about the need for racial representation in healthcare, his approach to drawing Black skin, and the role of creativity in medical illustrations.

HealthCity: You’ve said that you are motivated by a passion for equity in healthcare but also by the beauty of Black people. Why do you think medical illustration is such a powerful device for promoting these things?

Chidiebere Ibe: Because I’m in the medical field, I am making use of the tools and the skills that I have to advocate for what I believe in. If I were a singer, I would sing songs to advocate for what I believe in. Because I’m an artist—I’m a medical illustrator—I have to create art that would advocate for what I believe in.

My drawings are not just depicting skin, or the Black skin, but also showing how Africa looks, typically. If you go to my drawings, you would see some drawings that depict how Africa looks like. For example, I created a drawing of a child with measles. That drawing was a child sitting on a bicycle, heading to the farm to get food for the day. Now, that’s typical lifestyle of Africa. My drawings are depicting how Africa looks on a daily basis and also portraying the medical part of it.

HC: Some show children wearing accessories that are specific to a culture. Some of the facial expressions are very playful, too. There’s a creative, cultural side to many of your illustrations.

CI: That is also to show medical students that anatomy can be fun. I realize that people tend to remember things that are amusing, or things that make them smile, things that make them happy. For example, I drew a child, showing the intestine and the kidney and the child smiling and laughing. Now, anyone that looks at that drawing would smile. Viewers smile, and that’s already making you excited, and it makes it fun for you to read and to know what this drawing is about.

For those [illustrations] with the beads and the attire. Imagine, [as a medical student from Africa] I see my beads. I see those beads in those drawings, in that medical textbook. I would say, “Wow, I would love to read and understand it.” I could relate to that much better.

HC: The lack of darker skin tones in medical books is important because physicians need to recognize how conditions or diseases present in patients with different skin color. Like with dermatology, for instance. What’s your approach to illustrating such conditions?

CI: Most times, on the internet or in medical textbooks, there are no drawings with Black skin. Most are in white skin. After creating my model, I research, “How does this [condition] reflect on the white skin? If this looks reddish on white skin, it invariably means that it’s going to look a pale brown on Brown skin. I make this comparison, then I do some [more] research. Basically, that’s the workflow. That’s the process for how I create most standard drawings

For example, “COVID toe” on white skin looks very reddish, but on Brown skin it looks scaly and light brown. Those differences are things I’m working toward addressing. That’s pretty difficult for me, because sometimes [the drawing] can be wrong because there are no references, but in most cases they are right.

HC: What is lost when Black people don’t see themselves reflected in medical illustrations, whether they are in the healthcare sector or are patients?

CI: There will be a lack of confidence in themselves. A Black mother in the U.S. reached out to me. She said that she showed my drawings to her children, and her children said, “Whoa, I love this. I can read this now, because I see myself in this.” Because people see themselves, they have more confidence in studying [if they’re in healthcare]. People now love themselves, people now value themselves, and people now feel secure and safe when they go to hospitals for diagnosis.

HC: How does your work as an illustrator influence your training as a medical student?

CI: It has affected my learning process, because I remember mostly when I draw. There is an art in medicine that most people haven’t explored. I want to be a surgeon, and surgery has to involve a lot of creative thinking.

I also want to tell people that surgery is more realistic or more fun when it’s been applied from the artistic perspective. People who have made inventions in the medical field were people who were thinking creatively, people who were artistic and were able to think outside the box. For you to make an influence or to make a change in the medical field, creative thinking has to be there. That’s what art gives you an opportunity to do.

HC: The impact of your illustrations has had that quality of art, which I’m distinguishing here from creativity or artistic skill. I’m referring to the way that art can change perception or challenge established systems. People have even been asking you if they can buy a print of your viral illustration. How do you feel about your work having this type of impact?

CI: I feel quite overwhelmed because I never expected for the work to go viral. I had to dig deep to understand that people resonated with that work.

I feel so good that things are already [starting to become] normalized. It’s amazing to know that now our medical textbooks will be more inclusive. If a top [scientific publisher] like Elsevier reached out wanting to include my drawings in their textbooks, I believe the change is already here. And I feel so good about it.

I also feel that it’s no longer my project, it’s no longer my push. Because if the change should occur quickly or the change should stay for a long time, people should come together to make this happen.

It’s just amazing to hear people say a whole lot of things. Even people that are not in the health sector resonated with that drawing, because they feel that their skin color can now be seen. It’s for those who are Black and for people of color wanting to be heard. The [reaction to the] drawing just made me feel quite overwhelmed, quite emotional. I felt blessed. I felt that people could finally see themselves.

HC: What has the response been from other medical illustrators?

CI: It’s been amazing. It means so much that I’ve just been an illustrator for one year, and I’m creating such drawings—and with a computer mouse. Some are speaking about partnering with me to create more. It’s amazing to build a community with them.

This interview has been edited and condensed