Even After Overdose, Only 1 in 3 Young Adults Receive Medication for Opioid Use Disorder

October 3, 2019

Getty Images

Research highlights opportunity to intervene with adolescents, a group who's particularly vulnerable to addiction and overdose.

Young adults have been increasingly affected by the opioid epidemic. Data indicates that national drug overdose deaths nearly quadrupled between 1999 and 2016 in young adults between the ages of 15 and 24 years. As the opioid overdose death toll rises, it’s critical to acknowledge adolescence and young adulthood as an especially vulnerable period for addiction. Experts have suggested that distinct developmental differences predispose adolescents and young adults to substance use disorders that often persist into adulthood — making the age an opportune period for identifying developing substance use disorder and deploying strategic, timely interventions.

“Given that the reward systems are more advanced than inhibitory systems among young adults, it is imperative to engage young adults in treatment as early as possible to help prevent a use disorder or worse,” says Sarah Bagley, MD, a pediatrician and internist at Boston Medical Center (BMC) who specializes in addiction.

Previous nonfatal opioid overdose is a known risk factor for future overdoses, and research shows that medication is effective at keeping youth engaged in addiction treatment and preventing fatal overdoses. Despite the evidence, medication for opioid use disorder (OUD) remains significantly underprescribed among adolescents whose lives it could help save. According to a new study in the Annals of Emergency Medicine, 2 out of 3 young adults who experienced an opioid overdose did not receive medication afterward.

“It is imperative to engage young adults in treatment as early as possible to help prevent a use disorder or worse”

– Sarah Bagley, MD

Led by researchers at BMC’s Grayken Center for Addiction, including Bagley, and the Massachusetts Department of Public Health (DPH), the study provides important new data that can help increase access and time to medication for opioid use disorder for young adults who survive an overdose.

Researchers conducted the retrospective study from DPH data from January 1, 2012 to December 31, 2014. The study included 15,281 individuals who were 18 to 45 years old and had survived an opioid-related overdose in Massachusetts, as determined by an ICD-9 diagnosis code for opioid poisoning following an ambulance encounter, discharge from the emergency department, or inpatient or outpatient observation discharge.

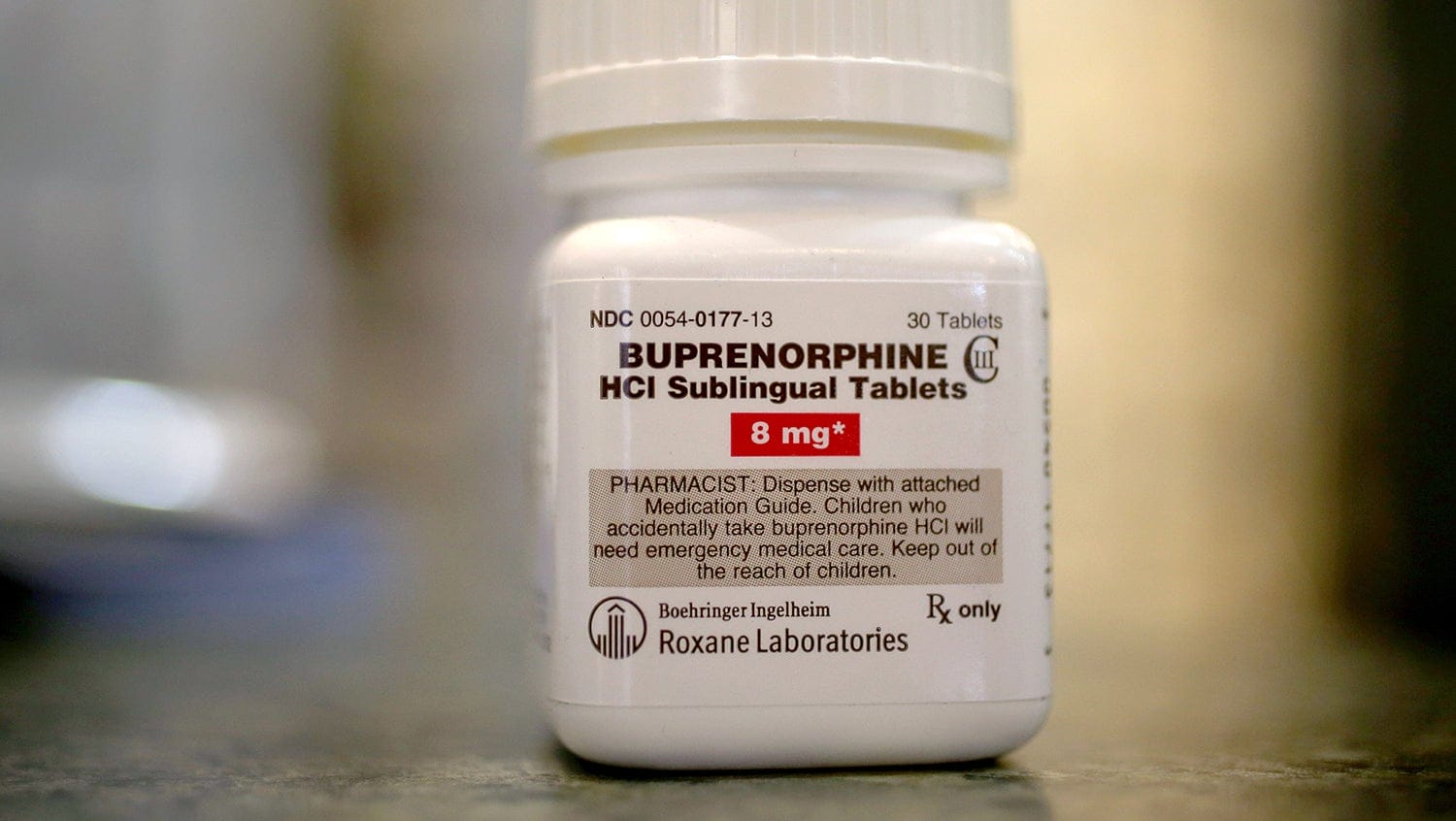

After their overdose, just 28% of 18- to 21-year-olds received naltrexone, buprenorphine, or methadone — the FDA-approved medications for opioid use disorder — compared to 36% of 22- to 25-year-olds and 26- to 45-year-olds. The median time to treatment was three to five months among all age groups, revealing the opportunity for improvement for engaging people in care promptly.

In addition, the study found that age appears to be a factor in the type of medication administered to treat opioid use disorder. Individuals younger than 25 were more likely to receive naltrexone, which is the least studied of the MOUD drugs and the option with lowest rates of retention. Individuals between 18 and 21 were least likely to receive buprenorphine. The 26- to 45-year-olds were more likely to receive methadone than the other two age groups, despite evidence that methadone has the best retention in treatment.

Additional studies could help clarify how providers and young adults choose a medication for opioid use disorder, including considerations such as insurance coverage and state regulation, and examine the feasibility of initiating medication for opioid use disorder in the emergency department, where people using opioids may first be identified, Bagley and her coauthors say.

“It is important that young adults who survive an overdose have access to medication, including when they are treated in the emergency department or in the hospital or outpatient settings,” says Bagley. “All of these encounters are critical opportunities to engage them in treatment, which can save their life.”