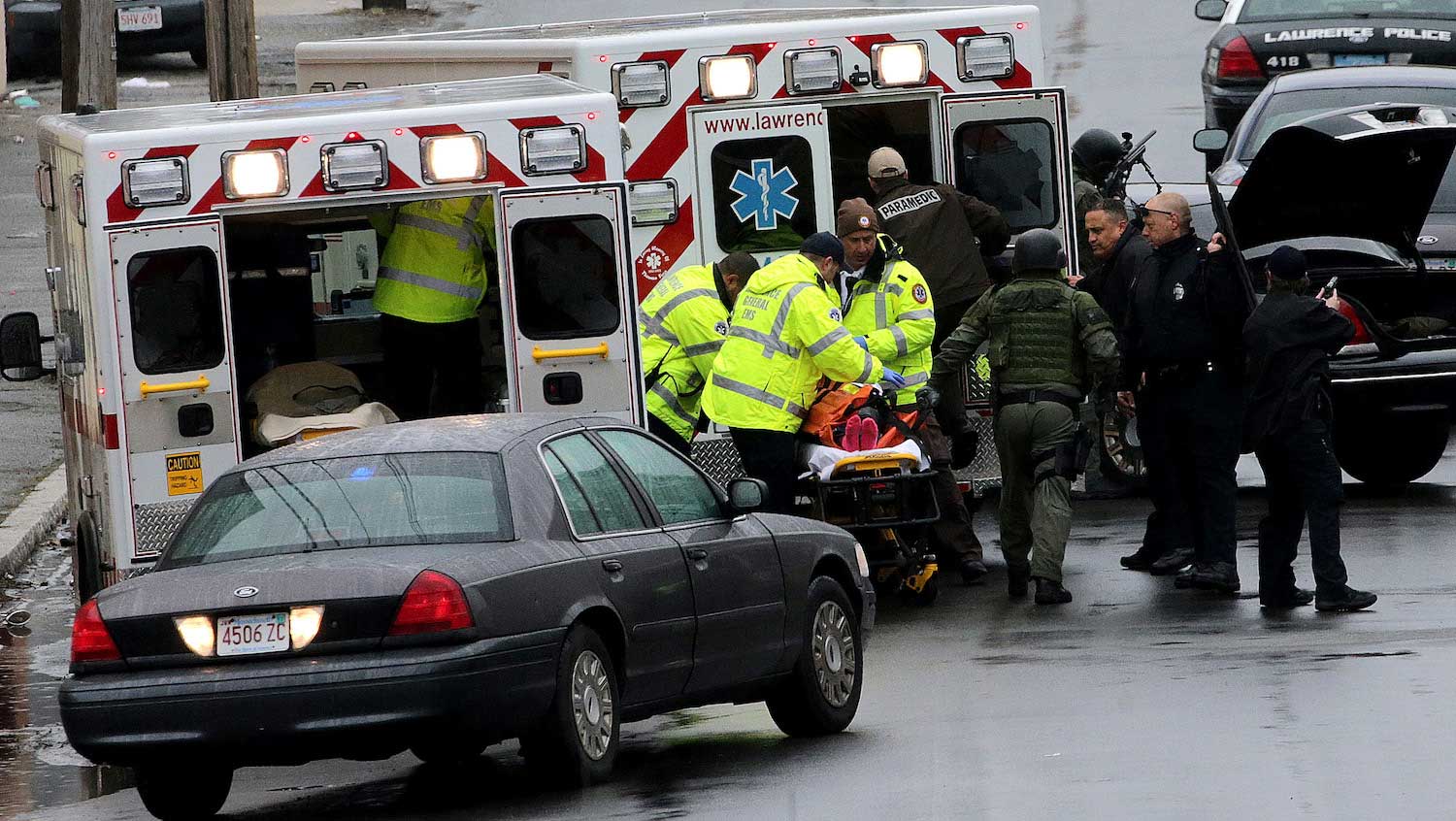

Getty Images

Medical and legislative understanding of gun violence is missing a key piece of information: the impact of nonfatal injuries.

In 2017, 39,773 people died from firearm injuries, and numerous others were wounded. While the people who survived may have fared better in the short term, researchers are now suggesting that firearm violence survivors, and the healthcare providers who treat them, haven’t yet dodged the metaphorical bullet.

Nonfatal injuries can have lifelong consequences in terms of the health and opportunities of the victim, but also costs for healthcare organizations. Gun violence survivors are believed to have an outsized impact on healthcare costs and the health of our communities, and yet our understanding of their long-term utilization, trajectories, and outcomes, and even their number, is shaky.

“Of course a gun death impacts a community,” says Miriam Neufeld, MD, a surgery and research resident interested in trauma at Boston Medical Center (BMC), which receives 80% of the bullet and knife injuries in Boston. “But from a healthcare economics standpoint, if someone is a survivor of firearm injury, that means you have ongoing care, long-term rehab, disability, maybe significant mental health issues. The ramifications are more diffuse.”

Neufeld and her colleagues at BMC and the Boston University School of Public Health are among the researchers now exploring the gaps in our knowledge of firearm injuries in hopes of uncovering the true public-health impact of gun violence.

“What’s burdening the system,” Neufeld says, “and how do we address it?”

Holes in the data

It’s estimated that firearm injuries affect three times as many people per year as firearm deaths do, but nobody knows the numbers for sure. While the Centers for Disease Control began tracking firearm deaths in 1979, it only began collecting information on firearm injuries more recently, in 2000. And even 19 years later, the CDC considers its own data unreliable.

Several factors limit the reliability of this data. First, the CDC injury data collects its information from a representative sample of 100 hospitals across the United States, but only 66 of these hospitals contribute firearm injury data — a pretty small sample size. And while the prevalence of most types of injuries varies little by location, firearm injuries tend to be concentrated in certain areas (depending on violent crime rates, for instance), which further limits the reliability of the CDC’s sample.

Compounding the problem is the fact that gathering the data is difficult even at the hospital level. While hospital regulations are explicit about how to code and report a traumatic death, they’re less clear about how to report traumatic injuries. And all of this is assuming that hospital data would catch all cases in the first place, but firearm violence often goes unreported, as people may avoid hospitals for fear of arrest.

Murky long-term outcomes

The number of firearm injuries itself captures only one part of the true burden of firearm violence. While trauma surgeons may be able to prevent deaths from gun trauma, firearm injuries can still have long-lasting impacts, such as physical disability and emotional trauma for the victim, their families, and their communities.

While there’s plenty of anecdotal evidence of long-term effects, such as the burden of decreased earning potential, accessibility problems, and PTSD, it’s another area of unknown in research.

“We pat ourselves on the backs because we saved their lives after a horrible gunshot wound, but what happens after they go home?” – Sabrina Sanchez, MD

“We’ve gotten really good at saving patients and getting them through the initial acute injury. We also know a lot about 30-day outcomes for trauma, but that’s where most of the research ends,” says Sabrina Sanchez, MD, a trauma surgeon at BMC. “There’s very little that has looked at these patients three months out, or six months out, or a year out. We pat ourselves on the backs because we saved their lives after a horrible gunshot wound, but what happens after they go home?”

While Sanchez notes that this gap in knowledge is typical of traumatic injuries, it’s particularly acute for firearm injuries. Physicians understand healthcare utilization and complications 30 days post-surgery, but after that, it’s unclear how patients continue to use health services, how well people recover physically and mentally, and what their ongoing quality of life is like.

Searching for insights

To better understand the long-term outcomes following firearm injury, Sanchez and Neufeld have joined forces to study the efficacy of psychosocial services for female victims of violent trauma. The project, funded by a grant from the Boston Trauma Institute, will take a retrospective look at BMC’s Community Violence Response Team, which offers crisis intervention, ongoing counseling and support, case management, and referrals to community partners for survivors of violence and their family members.

“The database that CVRT keeps is very important,” says Sanchez. “Even if a patient doesn’t have any medical issues they need to come to the hospital for, the case managers at CVRT do follow up with them. CVRT keeps a very detailed database of all of that information.”

The information will be helpful in determining patterns in patient outcomes and the efficacy of the care provided after a nonfatal injury in a way that other hospital data insights would not be able to.

Addressing the problem

Understanding the long-term outcomes is only half the battle, though — if someone gets injured, it’s already too late. Neufeld and Sanchez are thinking with an eye toward prevention with another project that focuses on what legislation actually reduces firearm injuries.

This research builds on previous work from the BU School of Public Health, which, using a database of gun-related legislation from every state since the early 1990s, found that three types of legislation are particularly effective in reducing firearm deaths: universal background checks, ID laws, and ammunition checks. Neufeld and her research team will now look at state-level data in states that have had dramatic changes in gun-related legislation to determine what specific laws impact firearm injuries.

The hope is to identify effective gun legislation, rather than what is termed “performative” gun legislation — laws that allow the government to say they are addressing gun violence issues, but that don’t actually address the root problems of violence. As firearm deaths are only one part of the burden of firearm violence, additional research on legislation’s impact on injuries will be a crucial piece of determining legislative effectiveness.

“We’re just starting to talk about gun violence as a public health problem, and how you balance individual rights with the public good is fundamental to public health,” says Neufeld. “Our research will help find what works, so we have a logical place to start the debate about how to find that balance.”