Getty Images

New research shows that the majority of patients don’t receive any further treatment in the month after a detox episode — but those who do are much more likely to survive.

The death toll from opioid overdoses continues to rise, all while evidence-backed treatments and interventions go underused. To close this gap, addiction experts are turning their attention to critical touchpoints — such as emergency department visits following an overdose, or being released from incarceration — as opportunities to initiate treatment and harm-reduction efforts.

Among the important encounters is opioid detoxification, inpatient programs for people with opioid use disorder (OUD) to manage withdrawal symptoms as they reduce their physical dependence on the substance. While detox can be an important step on the path to recovery, leaving detox also can be a dangerous time if it doesn’t lead to continued treatment.

People who enter detox programs often have severe OUD and are at a high risk of relapse when they leave. In fact, one study found that more than one-quarter of patients relapse on the day of discharge from their detox program and 65% relapse within the first month. Moreover, people leaving detox who don’t realize their tolerance has decreased may be more likely to overdose unintentionally.

“Detoxing without further treatment makes people vulnerable to opioid overdose,” says Alexander Walley, MD, an internist and researcher at the Grayken Center for Addiction at Boston Medical Center.

Further treatments that may prevent relapse and overdose — namely, initiating medication for OUD and entering residential treatment programs that offer therapy and transitional services — are a part of care for as few as one-third of people following detox. A lack of quantitative data illustrating the impact of these treatments has likely contributed to the ongoing insufficiency of detox programs in keeping people safe, substance-free, and most importantly, alive.

A new study led by Walley and published this week in the journal Addiction highlights the extent of the missed opportunity and the impact that medication and residential treatment can have on patient survival — especially when used in combination.

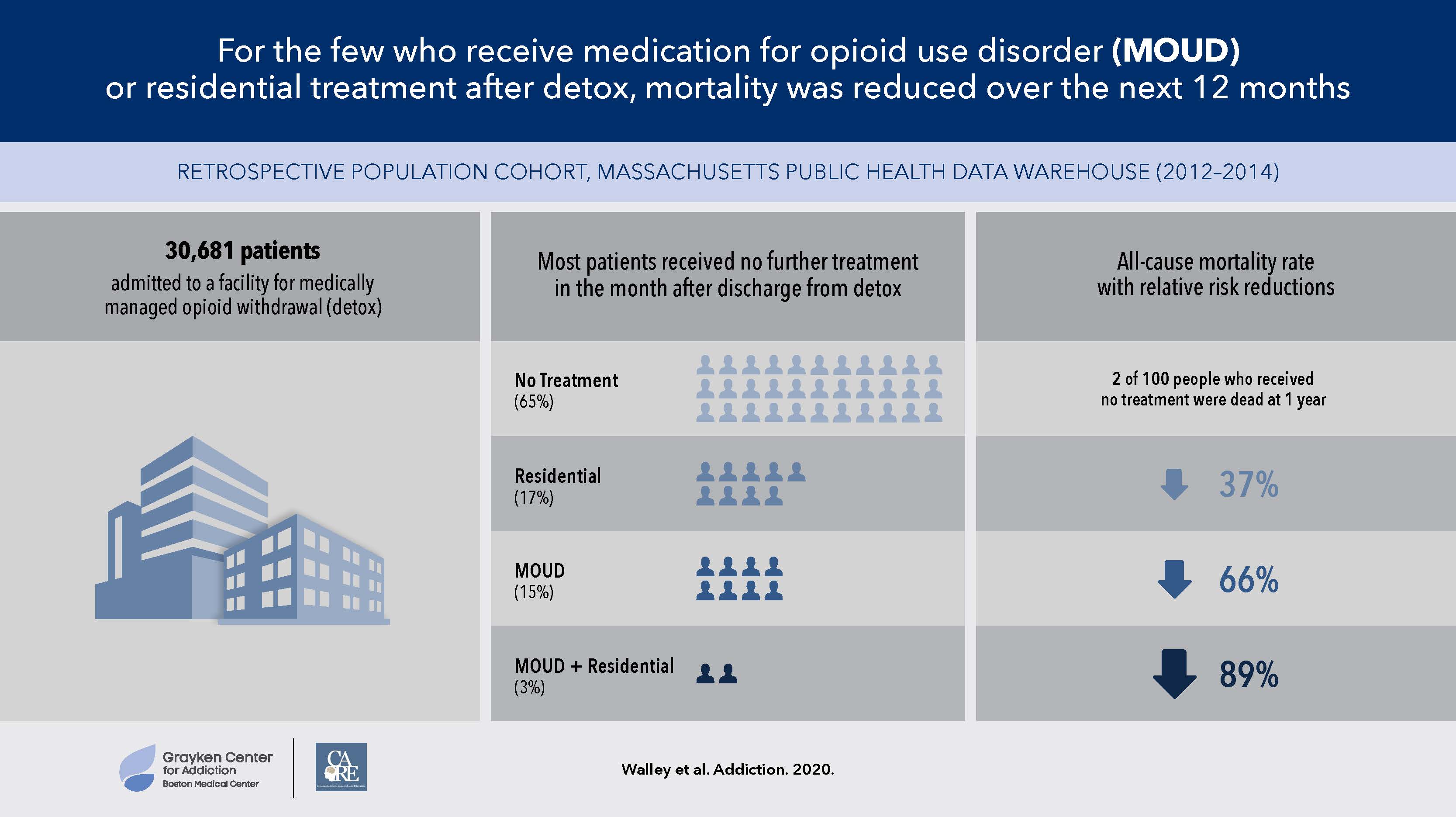

Using the Massachusetts Public Health Data Warehouse, a database that represents more than 98% of residents within the state of Massachusetts, the researchers performed a retrospective analysis of 30,681 patients admitted to a detox facility, in the first-ever study to use such a comprehensive data set to link OUD medications, inpatient addiction treatment, and mortality.

The study found that most patients did not receive further care in the year following discharge and that patients who did not receive any treatment in the month after a detox episode had the highest mortality rates. Among those individuals, 2% had passed away by 12 months post-detox.

Receiving further treatment in the month after detox, however, was extremely protective against mortality.

“Although a minority of individuals are linked to treatment after detox, those that receive further treatment, especially medication for opioid use disorder, have reduced rates of both opioid-related and all-cause mortality,” says Walley, a co-author of the study.

According to the paper, inpatient residential treatment was associated with a 37% reduction in mortality risk, while OUD medications were associated with a 66% reduction. The greatest mortality reduction, 89%, was seen among the few patients who received both medication and an inpatient residential stay within the month following detox.

While proper treatment is important for all people with OUD, these numbers suggest that it is particularly urgent for those who have just experienced a detox episode. The study findings also suggest that detox programs represent a huge area of opportunity for better serving this patient population.

To begin with, says Walley, providers should ensure that they’re providing education to their patients. Patients must be aware of the elevated mortality risks involved when they forgo further treatment after a detox episode, and all should be educated about overdoses and provided with a naloxone rescue kit at discharge.

Rethinking the detox model to shift the focus from “detox” to medication management, in which programs encourage patients to start and stay on OUD medications, could also have life-saving results, says Walley. The study authors propose that OUD medication should be the default pathway for all. Instead of needing to “opt in” to receive the treatments that could save their lives, as is the current practice, new best practices could dictate that patients would need to actively “opt out.” Residential treatment programs have not traditionally permitted patients to continue OUD medication while admitted, which is one factor that makes combined treatment less common.