Hepatitis C Treatment Uptake Hinges on Learning Directly from Patients

February 22, 2021

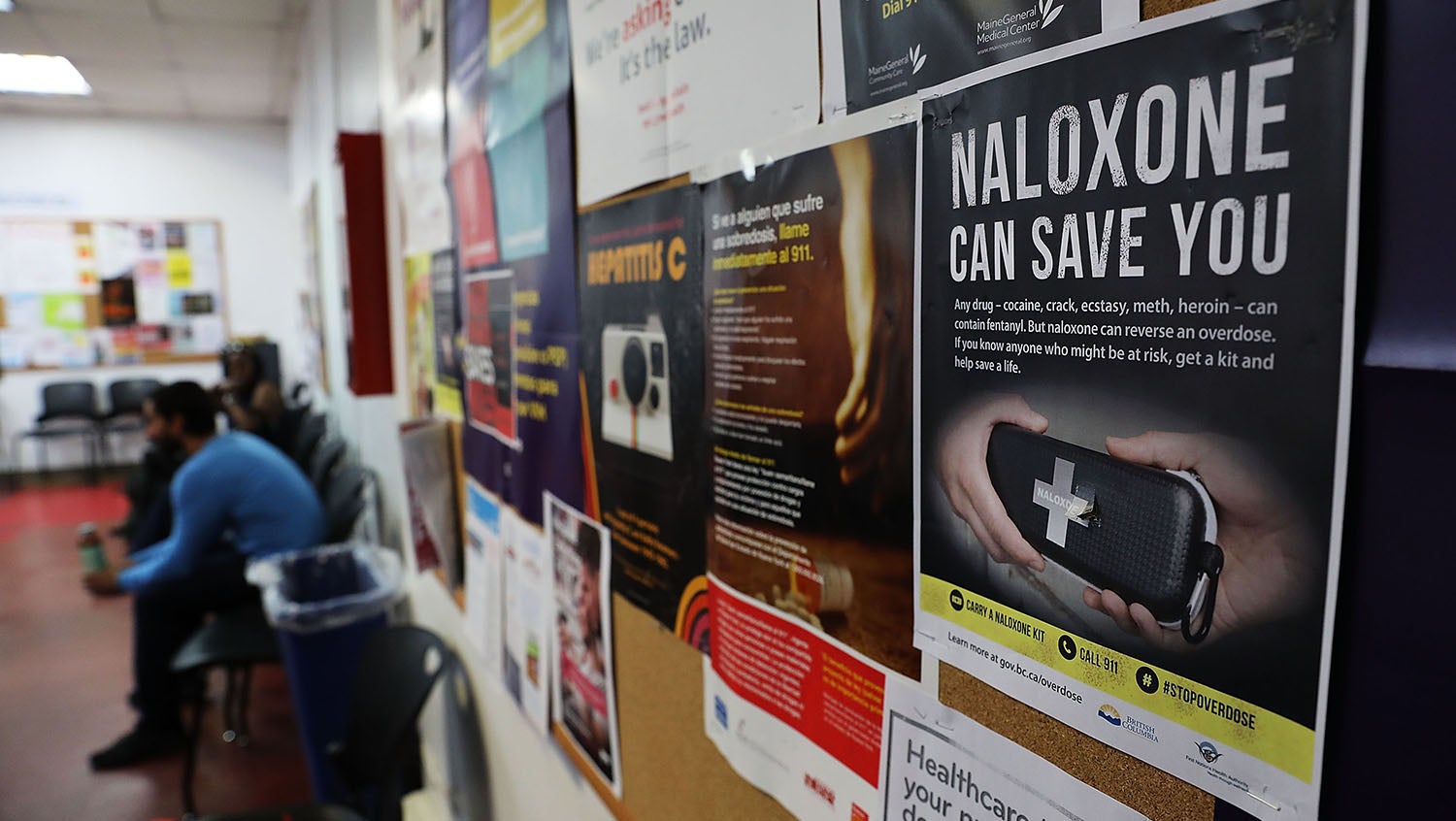

Spencer Platt, Getty Images

In a new study, infectious disease physicians engaged patients with hepatitis C and substance use disorder on how to best integrate comprehensive treatment into their lives.

The ongoing opioid epidemic in the U.S. has been both overshadowed and escalated by the COVID-19 pandemic. Its detrimental effects are direct, including opioid overdose deaths, and indirect, including the increase in hepatitis C virus (HCV) cases.

“Hepatitis C is a complication of injecting drugs, including opioids,” says Sabrina Assoumou, MD, MPH, an infectious diseases physician at Boston Medical Center (BMC). Experts such as Assoumou advocate for a comprehensive, integrative approach to treating hepatitis C, substance use disorder, and competing social needs, concurrently.

Assoumou noted that, as an infectious disease expert, the traditional training she received as a fellow did not involve substance use disorder. BMC has the first program in the U.S. that offers combined training in both infectious diseases and also substance use care.

“It has shown me that as an ID physician treating hepatitis C or HIV among persons who inject drugs, I can’t really do my job and do it well if I don’t integrate the two,” she said.

As a part of a new research study, Assoumou and colleagues sat down with patients at a drug detoxification center to learn firsthand the barriers that people with SUD face to receiving comprehensive care for HCV and how treatment options can better integrated into their lives. HealthCity spoke with her about what she learned.

HealthCity: What does the current state of hepatitis C treatment look like?

Sabrina Assoumou, MD, MPH: There is a known cure for HCV, but it is not being accessed by those who need it most. The treatment for HCV is a regimen that is taken for an average of three months to completely cure the virus and is well-tolerated by those who take it. Studies have shown that people with substance use disorder do just as well with treatment as those who do not — however, these patients typically require more support throughout the care process to make it most successful.

HC: How did you approach this patient-centered study on hepatitis C treatment uptake?

SA: To address any illness, you first need to talk to the patient and make them a partner in coming up with solutions. I want patients to tell us, if they had to build a solution for themselves, what is the innovative way that they would build it, if they had all the tools and were at the table? Having a patient-centered approach is definitely the way to build an intervention and an approach that would, at least, help in increasing the probability that it is going to be successful. It was so important to us to give patients with hepatitis C or who have substance use disorder a voice.

HC: What was the response from patients about being involved in the treatment plan?

SA: The importance of autonomy was really highlighted. A lot of participants underscored the idea that they didn’t want their clinician to make decisions for them; they wanted to know what the options were. They expressed that being forced into treatment paths that are not in line with their choices, desires, or needs would make them less likely to follow the clinician’s recommendation. There was a real desire to be part of the decision-making process to make sure that they’re more successful — this is so important.

HC: Did you learn about any common myths among people with SUD that impact HCV treatment uptake?

SA: There is a perception that insurance companies will only cover one round of HCV treatment; that people only get one chance, and if they use that opportunity and then relapse, they’ve missed their chance. That’s just not true. Addiction is a chronic illness. Patients may relapse for various reasons, but they still have an opportunity to get treated.

This myth has people waiting “until they’re ready” to consider hepatitis C treatment. We should be treating all patients for hepatitis C, even if they’re still injecting drugs. This is not only for their own health, but also for greater public health to reduce transmission.

Moreover, a lot of patients we spoke to thought that reinfection of hepatitis C is inevitable if they are still experiencing opioid use disorder. Patients feel like, “What’s the point of getting treated now if I’m only going to get re-infected again?” Reinfection is not inevitable. If we give patients comprehensive care in which we treat hepatitis C at the same time as treating SUD, we can keep them healthy so that they don’t relapse.

By listening to patients, we learned that in order for them to have success in an HCV treatment program, we need to first provide care for the substance use disorder. They’re thinking, “I have more serious problems to address.”

HC: What are some of the barriers to accessing HCV care that patients saw?

SA: In Massachusetts and around the U.S., to be able to access substance use treatment, you need to have an identification card, a Mass ID. This seems very simple but, unfortunately, because of various reasons — losing an ID, not having enough money to pay for the ID, not being able to go to the DMV — some patients were not able to access treatment. It’s the unintended consequences of regulatory measures that create bureaucratic barriers.

HC: What can be done to break down barriers to care and make it more accessible?

SA: The U.S. is not on track to meet the World Health Organization goals of eliminating hepatitis C because there has been a lack of providing access to treatment for people with a history of opioid use disorder and injection drug use. Even though we’ve expanded the locations where patients can get treated, patients are also looking for hepatitis C care in nontraditional settings where they feel more comfortable, where they already have a developed relationship with a community health worker, and where they feel like there is a more welcoming environment. These include places like substance use treatment settings, methadone clinics, and other places where they already go for care. Patients want us to come to where they are, as opposed to expecting them to come to us.

Moreover, once in treatment, we cannot underestimate the impact of a patient’s social needs. We have to address their social determinants of health. For example, housing is a major issue. A patient can show up to my clinic, and I can say, “I have a pill. I can cure you.” But if patients have unstable housing where they can’t keep their pills, it will be really hard for them to complete the course, even though it’s only three months. Providing a holistic approach where we take care of all the needs is crucial.

HC: What are the lessons from the study that are applicable to other processes?

SA: As a medical community, we often make the mistake of focusing on the cure without regard for the implementation. I think of the analogy between the hepatitis C treatment and implementation and the current COVID-19 vaccine. We’re good at doing the benchwork and the science. We came up with the cure for hepatitis C. We came up with a vaccine that’s 95% effective for COVID-19. But how do we actually roll it out and make sure that all the effort that is put into the science actually leads to a good execution and implementation down the line? That last mile. We have something that’s effective, but if it’s not reaching the people who need it the most, then what good is that?

This interview has been edited and condensed.