'If We Don't, It Is a Huge Miss': Researchers on Increasing Representation in COVID Clinical Trials

September 4, 2020

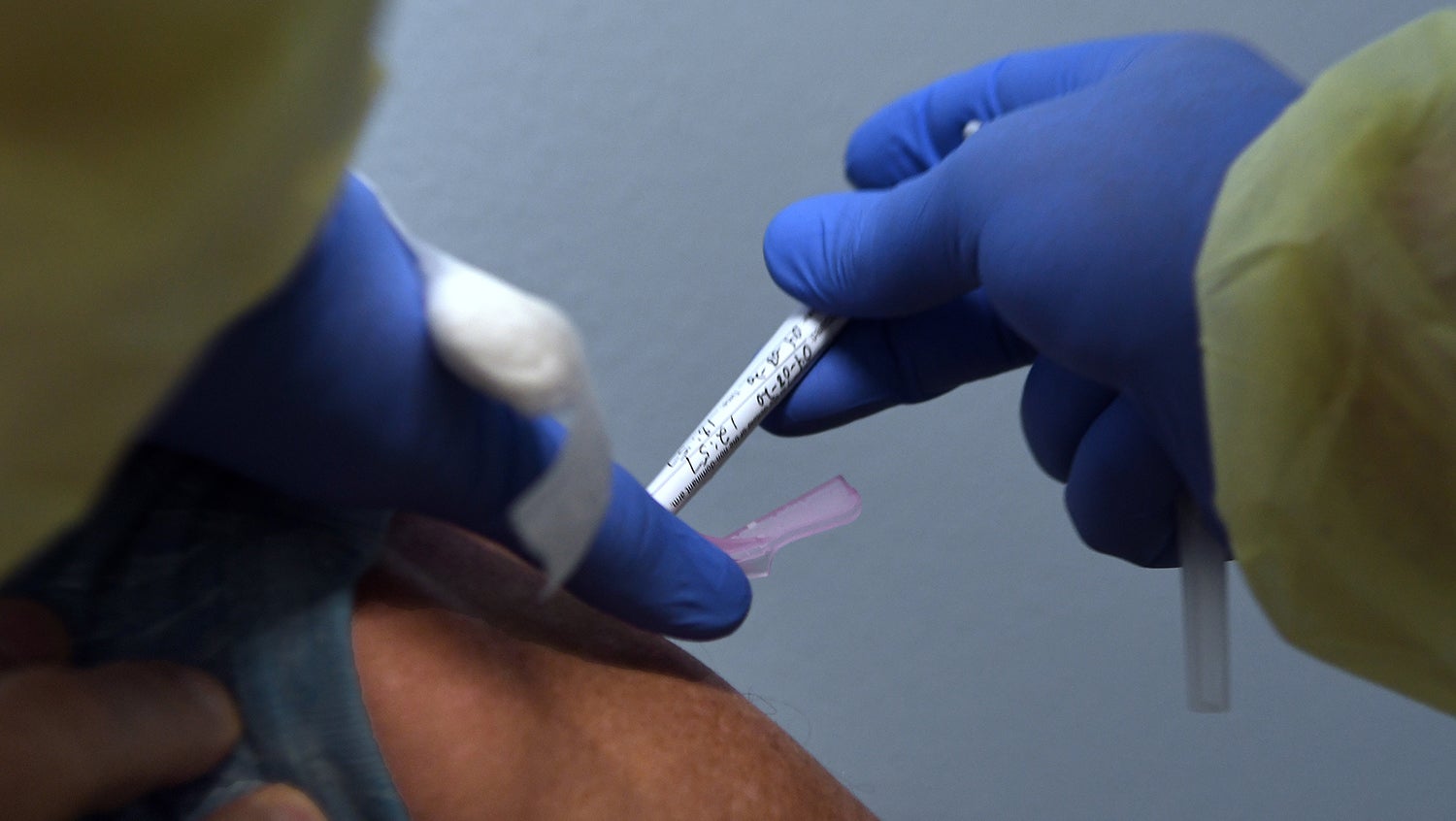

Getty Images

Researchers Tuhina Neogi, MD, PhD and Nina Lin, MD describe their COVID clinical trials and why engaging underrepresented minorities to participate is essential.

Given how disproportionately Boston Medical Center’s patients were impacted by the novel coronavirus (COVID-19), the safety net hospital is ensuring it plays a central role in advancing COVID-19 science and treatment. Groups that have been shown to be most vulnerable to the virus have also historically been underrepresented in clinical research studies, including COVID clinical studies, a pattern that is complicated by histories of medical mistreatment and trauma.

Since cases began to surge in Boston, BMC has been involved in 19 studies, with approximately 70% focused on COVID-19 treatment and the remainder centered on other areas such as data collection and testing.

We recently sat down with infectious disease physician and director of BMC’s infectious disease clinical trials unit, Nina Lin, MD, and BMC’s chief of rheumatology, Tuhina Neogi, MD, PhD, to learn more about their research efforts and to better understand the significance they bear for diverse patient populations.

HealthCity: First and foremost, why is diversity in research so crucial, and how can your research at BMC contribute to that?

Nina Lin, MD: BMC is in a unique space to recruit minority patients who have historically been underrepresented in research clinical trials, and engaging our patient population can fill an important data gap in the field. One example is with HIV research. Current first-line therapy for HIV infection, integrase inhibitors, seems to be having some unexpected side effects such as weight gain and metabolic disorders. Observational data seems to suggest this is mostly happening in African American and Hispanic women — who are completely underrepresented in all the clinical trials. We can help pharmaceutical companies and clinicians really understand the gap between what’s happening in real life and what has been shown in earlier clinical trials.

HC: How is diversity in research contributing to health equity?

Tuhina Neogi, MD, PhD: Clinical trials are an important part of health equity. Why shouldn’t our patients have the opportunity for promising therapies? A very important part of BMC’s mission in research is showing that we can do it ethically and in partnership with patients. We need to engage our communities so they can feel fully engaged as partners in helping to direct the research that’s needed for their communities. In many regards, research that involves our patients will be directly contributing to the understanding of health disparities and how systemic inequities contribute to adverse health outcomes.

HC: With regard to COVID-19 research, why is it so important to include safety net patient populations in clinical trials?

TN: COVID-19 is disproportionately affecting those who are vulnerable and they are having more severe outcomes. If we don’t offer trials to the people who are hardest hit and most affected by this disease, then it is a huge miss.

NL: Without their representation, clinical trials wouldn’t be applicable to the entire patient population in the U.S. They may not be applicable to inner city populations like we are treating at BMC because these individuals may present and respond differently from the white male population classically studied in trials.

It’s really critical we get the message across to have mandatory inclusion of these populations.

It’s really critical we get the message across to have mandatory inclusion of these populations. While other patients and other hospitals were initially offered the experimental drugs, [sponsors] were passing over BMC and a special population who is at exceptionally high risk for COVID-19 — people who are essential workers, people with lower socioeconomic status, people who are living in a crowded environment, and people who were in homeless shelters. It took a lot of advocacy, networking, and phone calls to bring these studies to BMC.

HC: What is the overall purpose of the studies you are leading?

TN: We are studying biologics [drugs that target the inflammation process in the immune system]. The general theme is that people who have COVID-19 pneumonia are having trouble with their breathing due to inflammation, reflected by some elevated markers of inflammation. Some people have mild symptoms because their immune system is successful in combating the infection. For others, as the body fights off the virus, the immune system goes into overdrive and they get hyperinflammation. The molecules that are part of that inflammation are known as cytokines. And those cytokines can end up doing the damage that worsens breathing and can result in the need for intubation. So these biologics are targeting certain aspects of that inflammatory cascade to try to mitigate the damage hyperinflammation can inflict when the immune system is working in overdrive.

HC: You’re researching canakinumab, tocilizumab, and combination tocilizumab/remdesivir. Could you briefly describe the trials?

TN: The study I’m running is a Novartis trial of a biologic called canakinumab that targets a cytokine, called interleukin-1 beta (IL-1ß), thought to be important in the hyperinflammation of COVID-19. The trial is focused on people who had COVID-19 pneumonia with hypoxia and elevated inflammatory markers.

Our patient population is quite unique. Despite the fact that we got into the trials late, we were still the fifth highest recruiting site in the country and 80% of our participants were non-English speaking. That’s just an incredible statistic and not heard of in typical clinical trials. Our informed consent form and study information were translated into a number of different languages — in total, we enrolled people who spoke four or five different languages in addition to English.

NL: The initial study I ran is called the BACC Bay Tocilizumab Study. Tocilizumab is an inhibitor of a cytokine known as IL-6 and had been used for many years by rheumatologists for treatment of rheumatoid arthritis. The study recruited people who needed oxygen with signs of early inflammation. The thought was, if we give this medication, we would stop some of that out-of-control inflammation that is damaging the lung and other end organs associated with people who are acutely and severely ill with COVID infection. That study finished enrollment across several Massachusetts sites, including BMC, [Brigham and Women’s Hospital] and [Massachusetts General Hospital]. The primary study teams are now analyzing the data.

The study I’m leading now is called the REMDACTA study, sponsored by Roche. It is similar to the first COVID study I ran but it’s [tocilizumab] in combination with remdesivir, with the rationale that treatment with an antiviral together with an anti-inflammatory agent may both decrease viral burden as well as the toxic cytokine storm. When the data came out for remdesivir treatment alone, it showed marginal effect on people who are close to being intubated with high level of oxygen requirement, but not late in disease with full respiratory failure. The rationale for the combination is that we could improve outcomes by both treating the virus and blunting the subsequent inflammation.

I’m also a co-investigator helping infectious disease physicians run an exciting Regeneron study that will study an investigational medication, an antibody that targets the viral spike protein that binds to the host cell. It has a broader inclusion criteria, so we hope to enroll more quickly than the other studies, many of which have very strict eligibility criteria bases as they are hypothesized to only benefit patients in particular COVID disease stages.

This interview has been edited and condensed.