Hospital Teams Juggling Sourcing and Usage to Prepare for Worst-Case PPE Demand

April 6, 2020

By Dave Wedge

Getty Images

As materials that are normally easy to stock become scarce, hospitals are forced to grow nimbler in creative sourcing efforts and more strategic in clinical use.

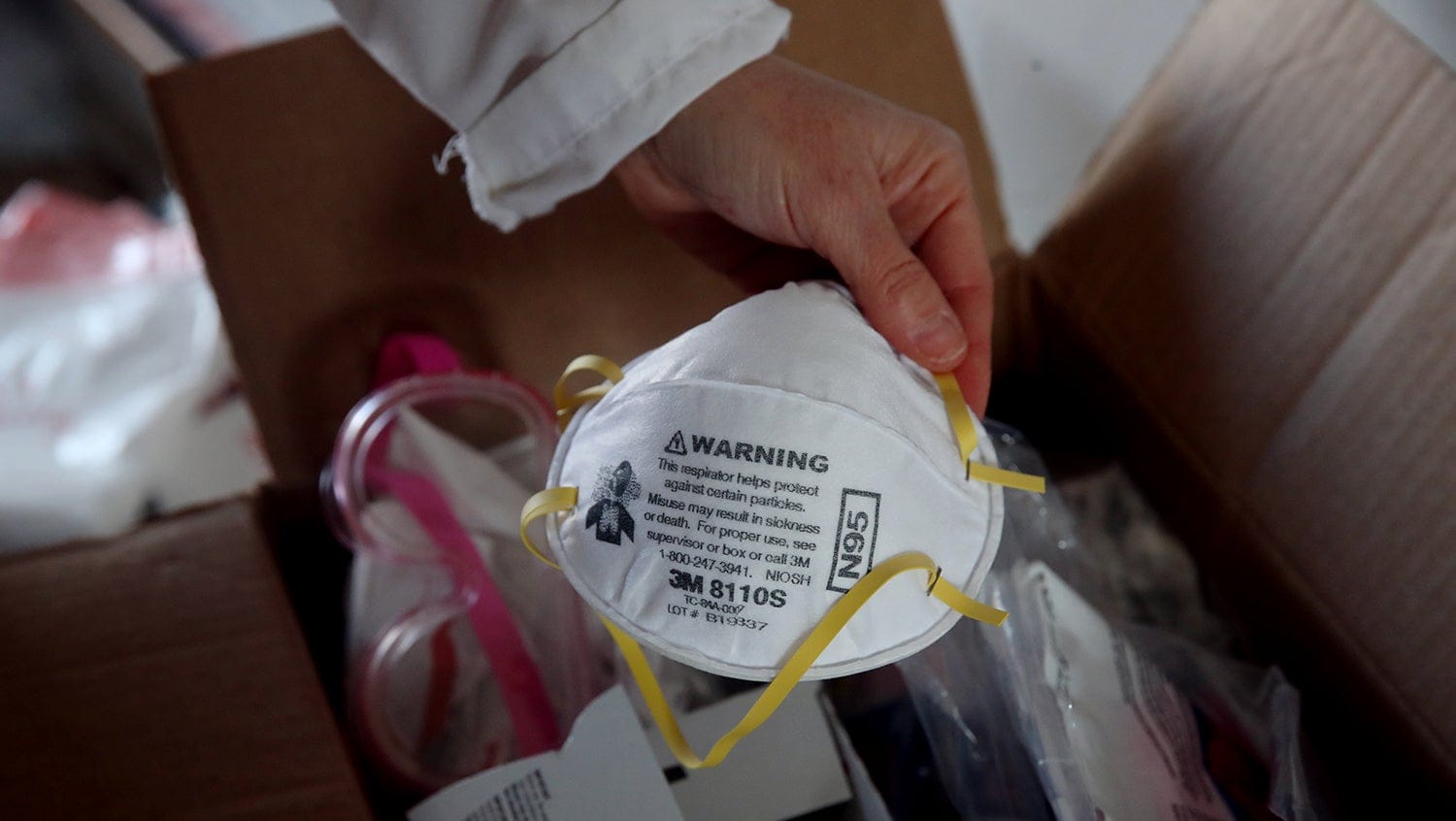

The coronavirus outbreak has hospitals and medical centers scrambling to find solutions to maintain essential supplies, especially personal protective equipment (PPE) for frontline staff.

Boston Medical Center (BMC), the safety-net hospital in the growing coronavirus hotspot that is the city of Boston, is no different. Even with greater-than-usual emergency preparedness baked into the hospital’s operations, administrators and doctors are working long hours to keep up supplies and meet demands. BMC’s logistics coordinators and medical staff are constantly modifying procedures, shifting resources, and reaching out to vendors to help protect nurses, doctors, and other staff responding to the pandemic.

“We’re actively searching for more stock so that we don’t get to a place like New York is at the moment, where people are really desperate to find PPE,” says Ravin Davidoff, MB, BCh, senior vice president of medical affairs and chief medical officer at BMC. “We’re trying to keep ahead, but it’s hard to predict. The surges occur and you have to activate very quickly.”

On the frontlines of this logistical battle is David Maffeo, the hospital’s senior director of support services. Maffeo is spending countless hours every day monitoring usage, checking inventory, and scouring the world for vendors to keep supplies coming in as the usual avenues are depleted.

It’s a delicate juggling act, says Maffeo, and one he hopes will allow BMC to handle the anticipated patient surges.

The sourcing ‘shell game’ for an infinite need

Surgical masks, which are now required for everyone on the BMC campus, are a top priority. Maffeo received a shipment of 100,000 last week, and more are expected on the way. While the number may seem large, Maffeo and Davidoff are quick to point out that masks go shockingly fast. The backstock should be enough only for the next several months, according to projections. Maffeo is cautiously optimistic — until the delivery arrives in the next week or so, he’s continuing to craft backup plans.

“Until it’s physically in our dock, I will not feel comfortable,” he says. “People are getting really creative based on what they can and can’t get. Nobody in the country is getting their regular deliveries, so you’re playing a shell game every day. That’s the way of the world right now.”

Maffeo indeed has had to get creative. He has had trouble buying disinfectant wipes from vendors, but tracked down 300 cases in New York. When delivery would have been too late, he hired a courier to drive there and pick them up. He’s on a constant hunt for isolation gowns and hand sanitizer and is working on securing more ventilators. They’re evaluating models daily to plan ahead so stockpiles aren’t depleted and nurses and doctors aren’t left without PPE, as has happened around the world and in New York.

“We’ve done a lot of modeling, looking at a worst-case scenario over the next 150 days and what that means in the world of supplies. And we’re trying to build up supply inventory so we don’t have to worry about it,” he says.

He’s looking to buy N95-type masks called KN95s from China, and has received 100,000 from GE Americares. Even with strict conservation efforts, the hospital churns through 1,000 N95 masks per day. At surge, which is anticipated three to four weeks away, daily use could be three times greater — paring a generous 100,000-mask donation down to just a thirty-day supply.

A culture of emergency preparedness

The hospital learned many lessons about patient surges during the 2013 Boston Marathon bombings, and BMC’s Incident Command Team conducts drills regularly. While no one saw a disaster of this scope coming, all the drills, logistics analyses, and planning have put the hospital — often viewed as the resource-constrained institution in the area — a step ahead of many others during the evolving crisis. What’s more, many of the drills are run in collaboration with other hospitals in the area.

“We have a great group of hospitals in the city that we work closely with, so that helps us when you look at bandwidth and sustainability,” Maffeo says. “Everybody is sharing best practices, what they’re learning, what type of PPE that they use, what’s worked … Everybody’s in the same boat.”

Donations are helping the cause. Ford Motor Company, which has modified some if its manufacturing plants to make PPE and other medical equipment, recently donated 6,000 face shields to BMC. The hospital is also talking with New Balance and Massachusetts Institute of Technology, both of which are now making masks, face shields, and other PPE. BMC’s philanthropy department is busy as well, accepting financial contributions and facilitating equipment and gear donations.

“It’s a daily struggle, to be honest. The supply chain team led by Scott Rutledge has spent countless hours talking to manufacturers, vendors, and we’re negotiating,” he said. “There’s a whole team here that is doing a herculean effort to make sure that this goes the way we hope it goes.”

Decreasing demand within the hospital

On the clinical side, changes to normal patient care protocols are being implemented to minimize the burn rate of PPE. There are “donning and doffing” sessions seven days a week to train staff on how to quickly, efficiently, and — importantly — safely take on and off their protective gear.

Attendants, residents, and other frontline staff are using buddy systems to back each other up to shrink the potential for gaps in treatment. Physicians and attendants are testing iPads and increasingly using telephones to check in with patients to reduce human contact and potential exposure. Davidoff himself is seeing many of his patients daily via telephone.

“In some ways, this is forcing us to play catch-up pretty quickly,” Davidoff explains, nodding to the hospital’s rapid advancements in telehealth in recent weeks. “It’s actually been quite educational how much I can do with the patients and their families on the phone in a very effective and efficient way.”

The hospital has relaxed rules requiring physical signatures for care and instead is allowing for verbal consent in another of many measures to reduce direct patient contact and opportunities for transmission of the virus.

Physicians and specialists from other disciplines are being redeployed quickly to assist in treating COVID-19 patients. Specialized units have been reorganized and non-COVID-19 patients are being moved to free up ICU and treatment beds. Doctors and nurses are localized in the hospital’s seven COVID-19 units, which is allowing for more direct communication than usual. The integration is also reducing the number of times that nurses, attendants, doctors, and residents need to go in and out of rooms.

All these efforts are reducing the usage of PPE by minimizing the movements of staff in contact with COVID-positive or COVID rule-out patients.

“We’ve rethought how we consolidate care on the wards and get only the absolutely necessary people going inside,” Davidoff says. “The care integration has actually improved, and I think in some ways, people are finding this more efficient, better patient care.”

While the challenges are immense and staff and supply chains are being put to the ultimate test, Davidoff believes there will be stark long-term lessons that will forever change how hospitals conduct business and lead to vast improvements in healthcare.

“This is a crazy time, but it’s actually a benefit in some ways that it has increased the speed at which we’ve been able to accomplish a lot of things,” he says. “There is a lot of opportunity here for us to think differently, do differently. We as an institution, and healthcare in general, are undoubtedly going to be different when this is all through.”