Addiction as a Learning Disorder: A Conversation with Journalist Maia Szalavitz

September 9, 2019

By Ray Hainer

Ash Fox / St. Martin's Press

The author of Unbroken Brain discusses our evolving understanding of addiction — and the implications for how we treat and prevent substance use disorders.

The way we treat addiction — as healthcare providers, as friends and family, as a society — is intimately bound up with the way we think and talk about addiction. Examples of this dynamic are everywhere. The stigma that haunts substance use disorders, the religious overtones of 12-step programs, and the war on drugs and the criminalization of drug use all bear the mark of the mental and moral frameworks we’ve used to make sense of an elusive and complex condition.

Addiction has variously been cast as a sin, a failure of will, and the product of a flawed personality. More recently, as the science and evidence have accumulated, clinicians and researchers have described addiction using concepts borrowed from genetic disorders, brain diseases, mental illness, and chronic medical conditions like diabetes or cancer.

In her 2016 book Unbroken Brain, Maia Szalavitz, a veteran journalist and author who has covered addiction for nearly three decades, proposes yet another model. Drawing on a broad array of existing research and her own experience with heroin and cocaine addiction as a young adult, Szalavitz reframes addiction not as a disease but as a learning and developmental disorder, closer to ADHD or autism than to diabetes or cancer.

In Szalavitz’s view, the learning disorder model helpfully knits together a number of disparate threads in our understanding of addiction. By integrating what we know about brain development and learning pathways, personality and temperament, the psychological underpinnings of compulsive behavior, and the tangle of social and environmental factors that influence substance use, the model provides a middle ground of sorts for the many competing analogies we’ve relied on to explain addiction.

Ahead of her visit to the Grayken Center for Addiction at Boston Medical Center, Szalavitz spoke with HealthCity about her take on addiction and the implications for prevention, treatment, and policy.

HealthCity: What are the key traits that differentiate the learning-disorder model of addiction from the disease model?

Maia Szalavitz: The rhetoric has generally been, “We’ve got to treat addiction like diabetes or cancer or anything else.” But the thing about viewing addiction as a disease is that we don’t know what kind of disease it is. If we see it as a neurological disorder like late-stage Parkinson’s or Alzheimer’s, we see people with addiction as not being in control of themselves and having no ability to change their behavior.

Traditionally, we’ve viewed people with addiction as either being under complete control of the drug or having complete free will. It’s somewhere in the middle. Because of the way addictive learning occurs, people with addiction have less control of their behavior, but they don’t have no control of their behavior — and the amount of control they have varies with the environment and a number of other factors.

We have a complex situation here, and if we treat addiction as a disease where the person has no free will, we’re not doing justice to anybody. We have to deal with that complicated middle. By placing addiction as a learning disorder, we can understand the developmental aspects of it.

HC: In Unbroken Brain you focus on adolescence as a pivotal stage in the development of addiction. Why makes it so important?

MS: Ninety percent of all addiction starts in the teens or early 20s. That’s a really important time for brain development. The brain is developing its ability to manage child-rearing, sexual relationships, love relationships. The prefrontal cortex is kind of finishing itself up and getting a handle on things like decision-making and responding to impulses.

Ninety percent of all addiction starts in the teens or early 20s. That’s a really important time for brain development.

And as kids develop, they’re encountering stuff in their environment that they have to learn to manage. If they have a predisposition to mental illness or an outlying temperament that makes them extremely into risk-taking, they’re going to be at very different risk than somebody who is exposed to drugs at 26 and has already learned how to cope with relationships, manage their emotions, and get through life.

The developmental perspective lets you realize how genes interact with environment. If you’re a kid like me who is temperamentally weird, you’re probably going to have difficulty fitting in socially and managing your emotions. I found that drugs worked really well for that — until they didn’t.

HC: You’ve been very candid about your own experience with heroin and cocaine addiction. How has that firsthand experience informed your work and your understanding of addiction?

MS: It’s always been very personal for me, trying to understand how I went from being a straight-A student to shooting up 40 times a day. That’s very real and very personal. At the same time, I understand that overgeneralizing from personal experience can be really damaging because what works for me may absolutely not work for you. That said, I’ve tried to use my experience to inform my expertise and understand addiction from every possible perspective.

The addiction world is so compartmentalized. There are people dealing with brain cells, and there are people looking at the sociology, the history, drug policy overall. Getting all of that expertise together is really important for dealing with a problem that cuts across biology, sociology, psychology, psychiatry, and many other fields.

I’ve tried to read widely across those fields, in a way that the people who specialize in them probably don’t have time to do. I look for the commonalities and the problems in explaining things, and I try to synthesize them in a way that makes sense and is at least congruent with the larger evidence in all of these areas. I try to bring that together and help people cross-pollinate.

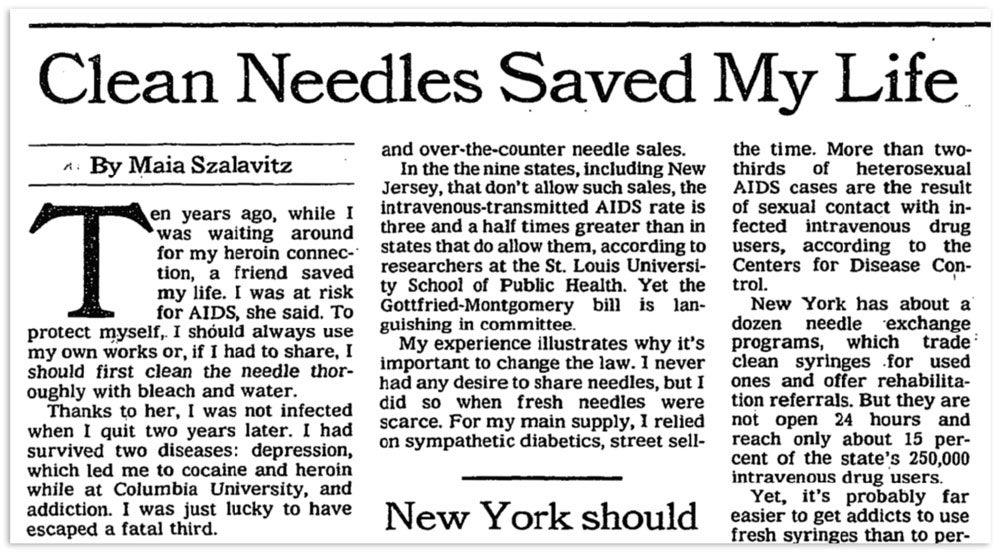

Over a 30-year career, Szalavitz has written extensively about addiction — including her own experience with heroin and cocaine — for publications including The New York Times, VICE, TIME, and The Atlantic. (NYT Archive)

Over a 30-year career, Szalavitz has written extensively about addiction — including her own experience with heroin and cocaine — for publications including The New York Times, VICE, TIME, and The Atlantic. (NYT Archive)

HC: Is that cross-pollination especially important to understanding a condition like addiction, versus, say, cancer?

MS: I think probably all of the fields could do with a bit more cross-disciplinary work, but addiction really does require it. When you reduce addiction to a rat in a cage and say, “Look — this rat will press the lever a hundred times and kill itself to get cocaine,” you’re leaving out the social aspect. And indeed, if you give the rat access to social experience, it will actually use less. They are social animals, just like us.

That’s not to say that animal experiments aren’t useful or that the only way to understand addiction is to put every single piece of context in. It’s just a matter of realizing that this particular condition, which requires somebody to acquire a particular substance and use it compulsively, can’t be reduced the way you might be able to reduce cancer. A cancer expert would probably tell me I’m wrong, and that you really do need to consider the social context there as well — the social determinants of who gets lung cancer, the treatment they get, whether trauma affects your risk. But it’s at least more obvious with addiction.

HC: Does seeing addiction through a developmental lens change how we should view the role of parents and other family members in recognizing the signs of addiction?

MS: One of the surprises when the book came out was that so many parents and relatives of people with addiction read it and said, “Oh I understand my addicted person so much better now. I have much more compassion.” I was really pleased with that — it was not what I was expecting. And I think it shows that if you’re a parent of a kid who is an outlier, temperamentally, you’re going to have to take some steps to protect them that you might not have to take if the child has more of a mid-range temperament. And knowing that can help you help them understand those tendencies.

At the same time, we understand more than ever before what policies help people thrive, and yet we have just crazy politics. You talk to these experts, and they’re like, “This is what a kid needs developmentally, but we’re in a climate of extremely high inequality and nobody’s getting that.” It’s very frustrating.

HC: You’ve reported extensively on the opioid epidemic and how it’s changing with the rise of stimulants, such as methamphetamine. What implications does the learning-disorder model of addiction have on how we tackle the epidemic as it evolves?

MS: Most serious addiction is poly-drug addiction — for me it was both cocaine and heroin. But the media and popular culture only seem to be able to demonize one drug thoroughly at a time. In the ’70s it was heroin, in the ’80s it was cocaine, and then it was opioids and now methamphetamine. And it just kind of swings back and forth.

The media and popular culture only seem to be able to demonize one drug at a time. In the ’70s it was heroin, in the ’80s it was cocaine, and then it was opioids and now methamphetamine.

Now, I do think there’s a real difference in opioids because they can be so deadly and because we have a good maintenance treatment for them. But rather than focus on one substance excessively, we need to ask again, “Why do people use drugs?” How do we reduce the harm around that drug use, rather than just assuming that if we stop people from using one particular substance, we’re going to solve this problem? Prevention that’s focused on teaching people how to be mentally healthy is way more important than teaching people, “This drug does this, and this drug does that.”

HC: You’ve been covering addiction for a long time. How would you rate our progress as a field and a society? Clearly, you feel some frustration, but what if anything gives you hope?

MS: I was watching the Democratic debate the other day, and it’s astonishing to me — I wrote about this, actually — that we have Democratic candidates trying to outrace each other to be more liberal on criminal justice and drug policy. I’m used to, “I’m going to be tough” — “No, I’m going to be tougher.” And here we have two leading candidates, Bernie [Sanders] and Elizabeth Warren, who are supporting safe-injection facilities. We have every single candidate with the exception of Biden favoring complete marijuana legalization. We have harm reduction becoming part of the national dialogue.

In the ’90s, everybody — including the media, including the Democrats and the Republicans — was completely convinced the drug war was the only way to deal with this problem. While the persistence of some of these narratives bothers me, we’ve come an enormous way since then. I have to remind myself of that when I get frustrated.

This interview has been edited and condensed.