New Buprenorphine Prescribing Guidelines Won't Solve the Opioid Crisis

May 18, 2021

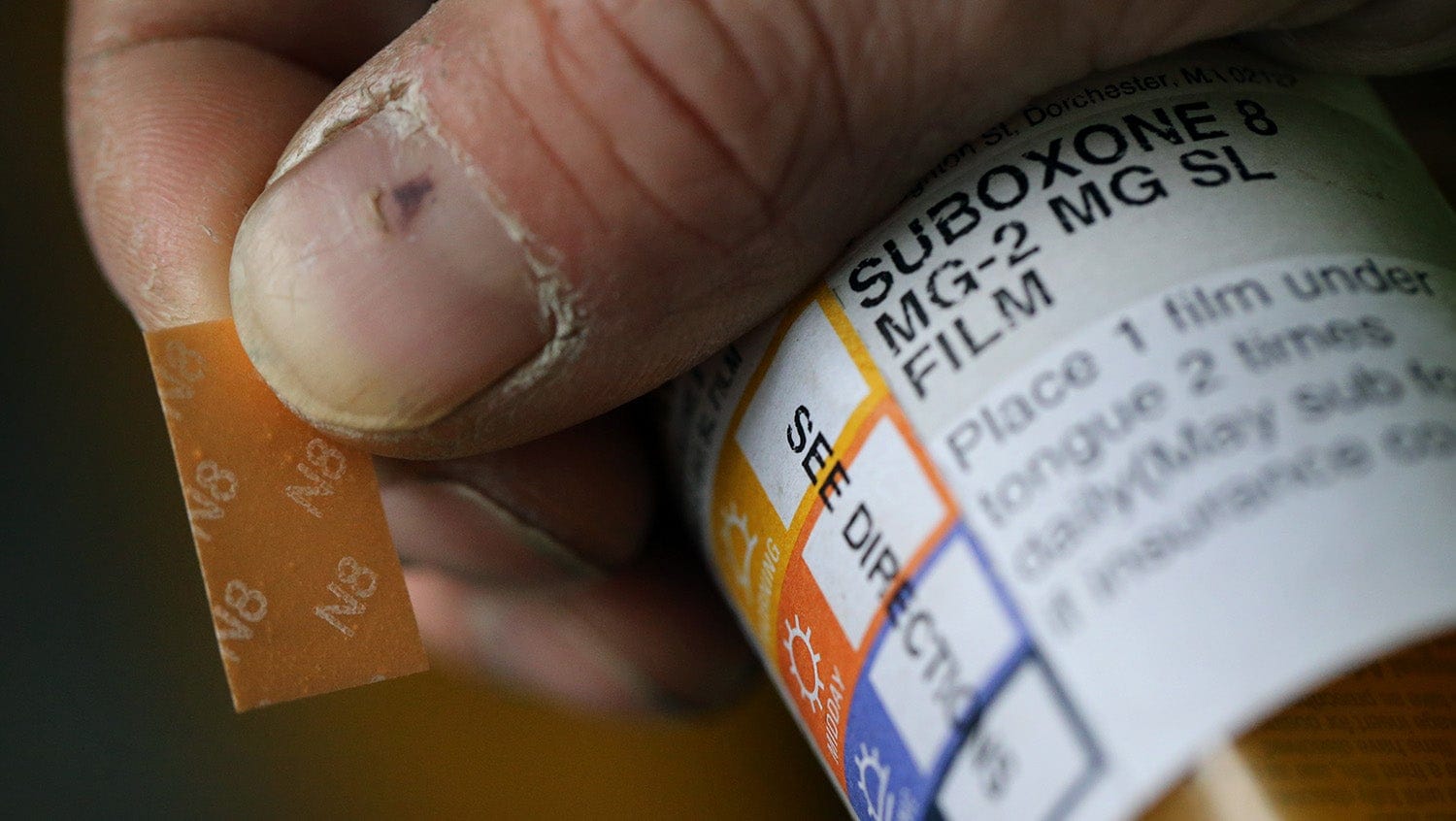

Boston Globe, Getty Images

Miriam Komaromy, MD, medical director of BMC's Grayken Center for Addiction cautions that the new rules don't go far enough in addressing opioid overdose deaths.

On May 12, the Massachusetts Department of Public Health released data showing that opioid overdose deaths increased by 5% in 2020, compared to 2019—marking a new peak for opioid-related overdose deaths in the state. But it’s not just Massachusetts. Preliminary U.S. federal data shows that, in the 12-month period that ended in September 2020, more than 87,000 Americans died of drug overdoses, reportedly driven by drug overdose deaths due to fentanyl and other synthetic opioids. That’s a 29% increase from deaths over the previous 12 months.

The surge in overdose deaths is likely exacerbated by the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic. Stressors such as job losses, health concerns, housing, quarantine requirements, social isolation, and changing family dynamics were prominent, but treatment was less available. Closures of clinic and inpatient programs for substance use disorder were common due to pandemic, and in some cities, ambulances were diverted from overcrowded and overwhelmed emergency departments.

To address the crisis of the opioid epidemic, the Biden administration announced last month it was changing guidelines for prescribing buprenorphine, an FDA-approved medication for opioid use disorder (OUD) treatment.

Previously, the U.S. government required physicians to first undergo a course of education and then apply for special “X-waiver” before being allowed to prescribe buprenorphine. The X-waiver is a sanctioned way to circumvent federal laws that otherwise make it illegal to prescribe controlled substances for the treatment of substance use disorders (SUDs).

Now, medical providers are able to prescribe the medication without needing to take the course of training that was previously required. However, providers still must have a Drug Enforcement Administration license and also apply for the X-waiver from the DEA, which registers their intent to prescribe buprenorphine.

While it is a step toward the right direction, Miriam Komaromy, MD, the medical director of the Grayken Center for Addiction at Boston Medical Center is careful to caution that it does not go nearly far enough to address the spike in opioid overdose deaths.

“It’s not going to be the solution we’re looking for,” Komaromy said to The Washington Post in late April, “to conquering the opioid overdose epidemic.”

Komaromy spoke with HealthCity about exactly what she meant by this and what would be more effective further steps to take to put a dent in the opioid crisis in the U.S.

HealthCity: You said that these new guidelines won’t be “the solution we’re looking for to conquer the opioid epidemic.” What are their limitations?

Miriam Komaromy, MD: While the new guidelines eliminate the training requirement, they do so only for providers who treat 30 or fewer patients—after which the education requirement is still in place. Another limitation is that the new guidelines still require that providers register with the DEA for the X-waiver. This requirement is not a trivial barrier. It has been used to create a special class of physician who is subject to much more intensive and intrusive monitoring by the DEA, which has served to dissuade a lot of providers from registering and treating with buprenorphine. Even though the DEA has backed off on this to some extent in recent years, it is very intimidating to physicians to draw extra scrutiny from federal agents.

HC: What are the pros to the new buprenorphine prescribing guidelines?

MK: The positive is that it increases access for providers who previously were not prescribing buprenorphine because of the training obstacle. Now, for up to 30 patients with OUD, providers are not required to take additional education.

It is important to note, however, that there is not a federally imposed education requirement in order to prescribe any other medication, and the original legislation had a discriminatory impact on people who have substance use disorders.

HC: What would a more robust solution look like to what was a record-setting year of opioid overdose deaths in the U.S?

MK: Eliminating the X-waiver and the special training requirements would be a logical next step. It would probably be somewhat helpful in increasing the number of medical providers who would provide buprenorphine treatment. However, stigma prevents many providers from doing this work, either because of their own attitudes or because the healthcare system where they practice treats this type of treatment as “optional.”

HC: What has been the hesitation to eliminate the X-waiver, like was very briefly enacted at the end of the Trump administration?

MK: The regulations for buprenorphine were mandated by an act of Congress (DATA-2000 legislation), and so it requires an act of Congress to change them. The Trump administration was trying to do an end run around this, but it got pushback. The hesitation and hold-up more broadly results from intense stigma related to substance use disorders and SUD treatment.

HC: Are there other policy changes the U.S. needs to undertake to effectively meet the needs of people with opioid use disorder and the clinicians who work with them?

MK: I believe the U.S. should decriminalize drug use—not drug selling—expand access to treatment, and expand access to harm reduction services. Treating addiction should be a standard part of medical training, and state medical boards should require this.

At the federal level, mandated education about addiction and addiction treatment should be linked to receiving a DEA license, and increased scrutiny should fall on prescribers whose prescribing patterns increase risk for developing SUDs, rather than imposing special scrutiny on providers who treat SUDs.