Community Narcan Training Extends Our Life-Saving Capacity

June 10, 2019

Yael Bermudez

Education and distribution turns community members into first responders and is key in overcoming the opioid epidemic, despite what some critics of the drug say.

Originally patented in 1961 by scientists searching for a treatment for constipation caused by chronic opioid use, naloxone quickly began being used for a markedly different purpose — as the premier antidote to opioid overdose.

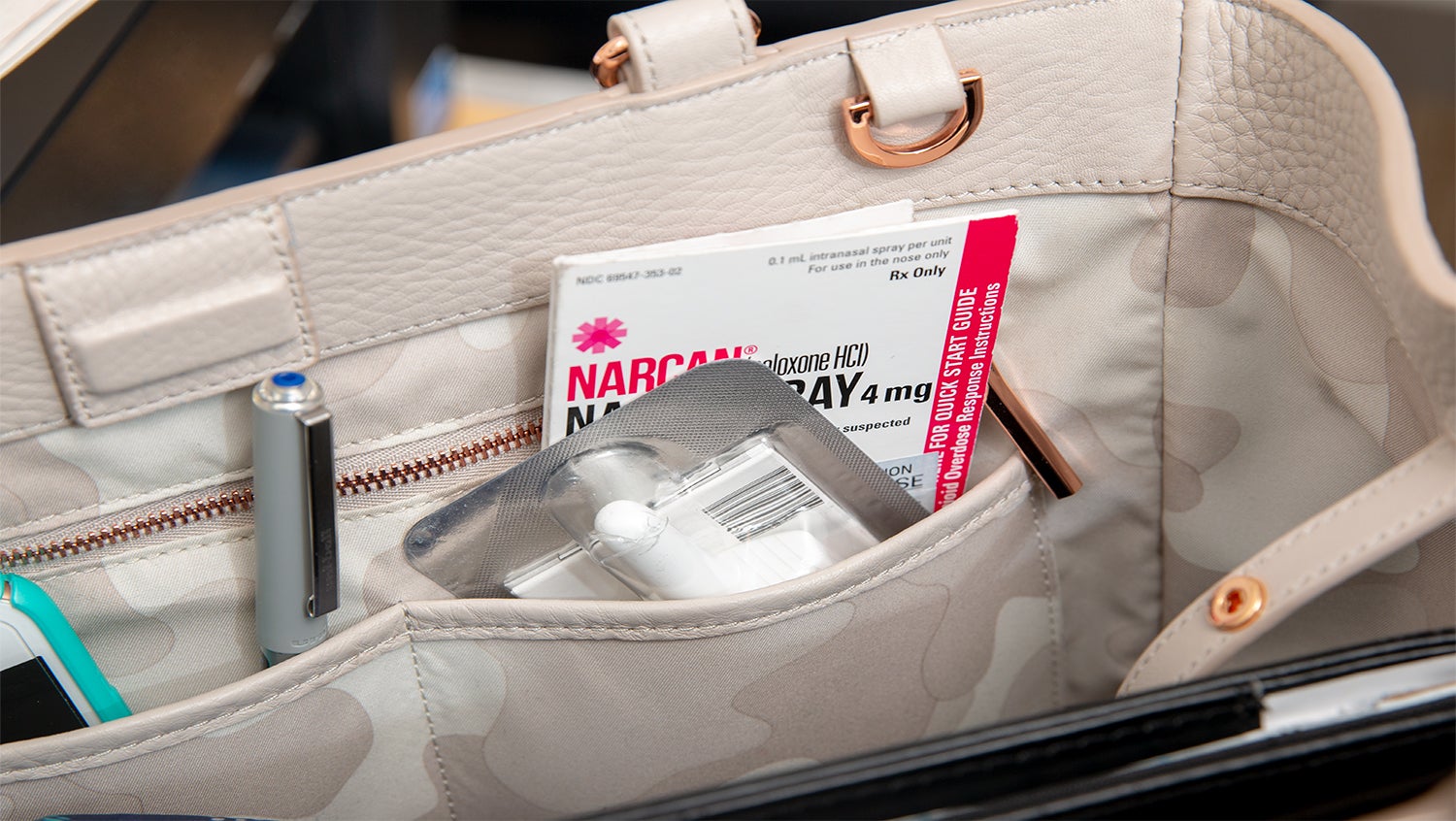

But it wasn’t until the last decade, as the opioid crisis snowballed into an epidemic of unprecedented magnitude in the US, that naloxone began making headlines, and often controversial ones. Some critics of naloxone — also referred to by brand names Narcan, Evzio, and Nalone — have suggested that it enables people with substance use disorder to use drugs without fear of a fatal overdose.

Alex Walley, MD, MSc, wants to put that argument to rest.

“Naloxone not only reverses an overdose, it reverses the euphoria and can even cause withdrawal. It’s the last thing that people who use opioids would want,” says Walley. “The only thing it enables is saving lives.”

How naloxone works in the opioid epidemic

Naloxone is an opioid antagonist. In simple terms, it can quickly go to the receptor site where an opioid such as fentanyl, heroin, or oxycodone is active and knock the opioid off. It then sits on that receptor so the opioid can’t bind and cause the overdose to recur.

Walley, the director of the addiction medicine fellowship program at Boston Medical Center — one of the four sites headquartering NIDA’s recently-announced $350 million study — considers naloxone one of the cardinal tools in curbing the epidemic and is a staunch proponent of making it widely available.

In fact, naloxone education and distribution play an important role in the study, called HEALing Communities, which is designed to accelerate effective interventions in 66 communities across New York, Kentucky, Ohio, and Massachusetts and create a national model for stemming the opioid epidemic. Naloxone is so important because administering it can do no harm, but a whole lot of good. While it can reverse an overdose, it has no effect on someone without opioids in their system.

Narcan training is a community need

Wilfredo, 56, is a resident of Dorchester, Massachusetts. Earlier this year, he and his mother discovered his brother in dire straits in their Dorchester triple-decker. Wilfredo served in Afghanistan and Iraq, but he says that nothing could have prepared him for what he saw that afternoon in May.

“My brother was stiff. He was pale. His eyes were turned to the back,” he recalls. “My brother was dead.”

Wilfredo’s brother was actually experiencing a severe overdose. It took firefighters and the EMTs working on him more than 30 minutes and multiple doses of naloxone to bring him back, all while Wilfredo could do nothing but watch.

While it’s important for first responders to be trained, Walley underscores the importance of training and getting naloxone in the hands of community members — especially given the potency and prevalence of fentanyl, a highly lethal synthetic opioid.

“It’s really important that the first person who finds somebody overdosing knows what to do,” said Walley. “Most of the time this is the person’s friends, family, or a person that they use drugs with, so those are the people who really need to be equipped with naloxone.”

Wilfredo, who hadn’t yet been equipped, wasn’t going to let it happen again. The day after paramedics revived his brother, Wilfredo attended a naloxone training hosted by BMC. He left with a naloxone prescription in hand and the know-how to help should another overdose occur.

Harm reduction overrules stigma

Scenarios like Wilfredo’s happen all across the country, and preparing for repeat overdoses is a reality that requires evidence-based medical intervention, not stigma.

Despite the medical acceptance of the neurobiology of addiction, judgments of morality and character still come into play when it comes to treatment options for people with opioid use disorder (OUD). Michael Botticcelli, director of National Drug Control Policy for the Obama Administration and executive director of the Grayken Center for Addiction, explains that stigma remains a significant barrier to evidence-based treatments such as naloxone. People with substance use disorders should have access to healthcare for their disease, but public perception often stands in the way of evidence supporting medical treatment.

The best approach, Walley says, is to combine overdose risk reduction and safety with medication for opioid use disorder, which includes the FDA-approved methadone, buprenorphine, and naltrexone. The fact that these treatments exist doesn’t negate the need for overdose reversal medication, however.

“Addiction is a chronic relapsing condition. So even though we have treatments, people who don’t have the means to stop or aren’t ready to stop will continue to use. While they continue to use, we need to keep them as safe as possible,” says Walley.

Increasing naloxone access for all

It’s more important than ever to get naloxone into lifesaving hands. According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 130 Americans die every day from an opioid overdose. In fact, the odds of dying from an accidental opioid overdose (1 in 96) recently surpassed the risk of dying in a motor vehicle accident (1 in 103).

While addiction doesn’t discriminate and impacts all populations, addiction and OUD are undoubtedly framed by cultural inequities and disparities. As with most health problems, people who are marginalized or who don’t have the same opportunities as others are going to be affected by OUD more severely and at higher rates than others.

To continue increasing access to naloxone, understanding these health disparities will be critical and something to which the HEALing Communities research teams will pay close attention.

Walley says we should look to naloxone as one of the primary interventions to help stem the opioid crisis. By preventing fatal overdose, we buy more time to help get people with substance use disorder into evidence-based treatment and, in turn, keep more people alive.

“People with opioid use disorder have to survive in order to get better,” Walley says. “Naloxone keeps people alive and gives them a chance.”