Mobile Medicine: How a Pediatric Vaccination Van Has Upended the Idea of Care

June 9, 2020

By Meryl Bailey

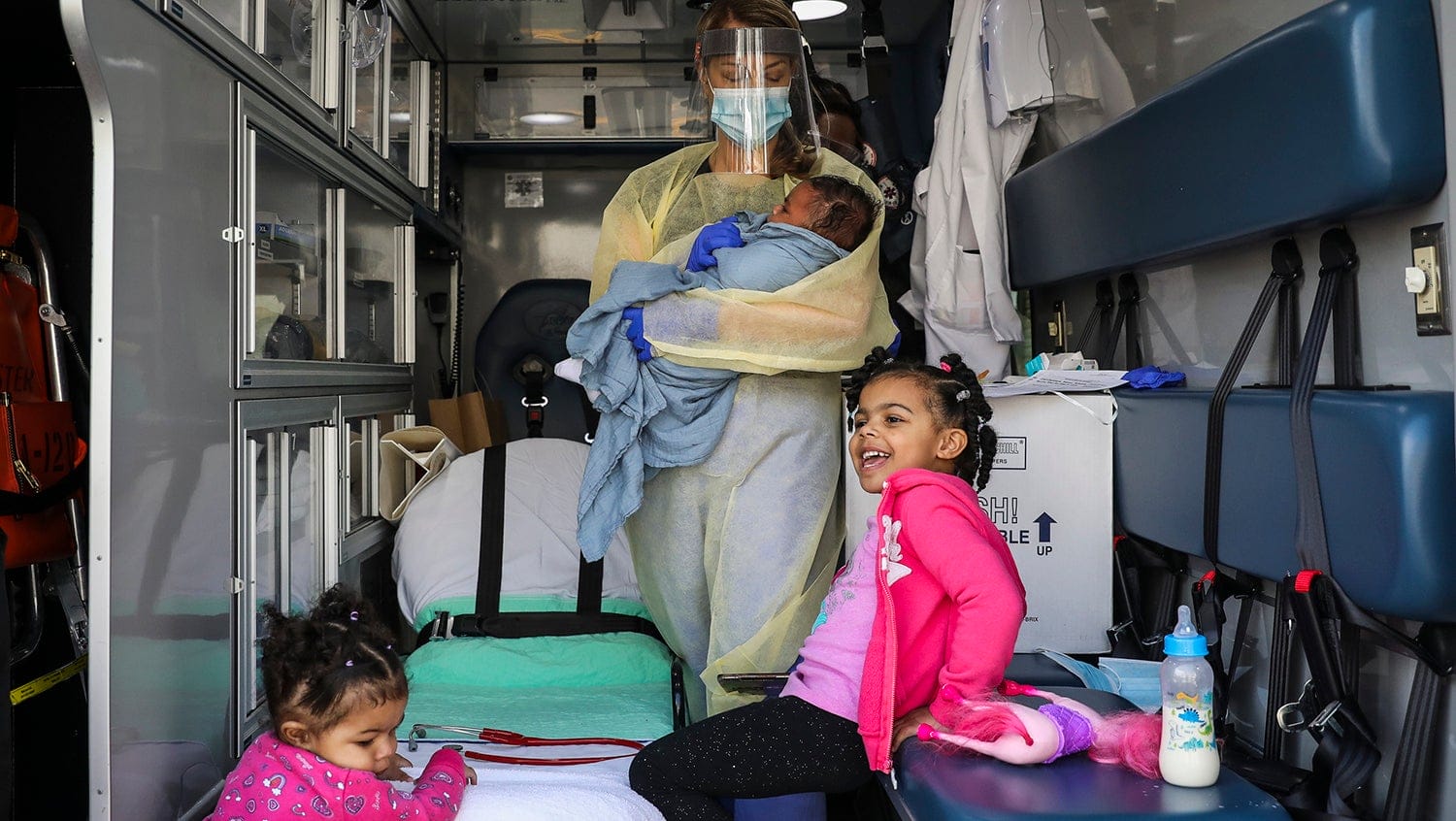

Boston Globe via Getty Images

In the face of the COVID-19 crisis, a mobile pediatric unit makes modern-day house calls and opens the door to a new way to provide care.

Days after the governor declared a state of emergency in Massachusetts and the state’s medical community braced for an impending surge of coronavirus cases, Eileen Costello, MD, chief of ambulatory pediatrics at Boston Medical Center (BMC), found the halls of her busy pediatric clinic eerily quiet. On average, 6,000 children typically receive check-ups in BMC’s department of pediatrics each month. With the new silence came a sense of foreboding. Her littlest patients were missing critical vaccinations necessary to prevent highly infectious diseases. The clinic’s empty hallways signaled that a new outbreak could soon be on the horizon.

Costello has every reason to worry. There has been a resurgence in vaccine-preventable diseases in the United States. Last year, a spike in measles cases threatened the nation’s elimination status — 1,249 measles cases were reported, the most in a single year since 1992. Before widespread immunizations, measles was a leading cause of death among children worldwide, and it is far more contagious than coronavirus.

“You can get on an elevator two hours after someone has gotten off and get measles from them because it’s just so contagious,” explains Costello. “And you have to have a high rate of measles vaccinations to protect the population. It has a 95% immunization threshold.”

Measles isn’t the only concern. Whooping cough (pertussis), pneumococcal disease, and hepatitis, among others, are extremely dangerous infections in babies and toddlers. Across the nation, vaccination rates dropped precipitously in March. Under stay-at-home orders and fearful of the pandemic, families were not coming into the hospital for these essential vaccines. Costello wondered if instead, she could bring a medical team to them.

A simple plan requires a monumental effort

The plan was simple: target children aged 15 months and under in the highest-need Boston neighborhoods of Dorchester, Mattapan, and Roxbury and deploy a healthcare provider to these families’ homes for well visits and vaccinations. Finding a vehicle outfitted for medical appointments, however, was a difficult task. After many phone calls and dead ends, the answer came through a generous donation from Brewster Ambulance Service. With emergent visits down across the state, the company saw the opportunity to use sidelined vehicles and keep ambulance drivers employed through this unique outreach.

Even with a vehicle at the ready, planning modern-day house calls proved no easy feat. Costello and her coordinating team, which included pediatrician Sara Stulac, MD, and BMC’s pediatrics nursing director Tami Chase, RN, had to cut through mountains of red tape amid a pandemic, engaging state and city stakeholders and coordinating with the Massachusetts Department of Public Health Immunization Division to order vaccines and ensure their safety on the road. Vaccines need to be kept cold to maintain their maximum effectiveness, and CDC guidelines do not allow the use of mobile refrigeration units. Each day, nurses had to carefully pack the required vaccines into Styrofoam coolers with chilled water bottles and bubble wrap to meet temperature parameters according to CDC specifications.

“It seems archaic, but it works surprisingly well,” remarks Chase.

Planning a weekly schedule of patients and mapping efficient routes through city streets is also a massive administrative effort. Nurses, patient navigators, and administrative assistants were tasked with coordinating vaccine schedules, grouping patient visits by community, synchronizing sibling check-ups, and matching the language needs of patients with language-concordant providers. If possible, patients’ regular pediatricians were matched for their house calls. The extra effort to coordinate providers with their patients was doubly rewarding, notes Chase.

“We were really struck by the amount of fear that our families were having about leaving their homes and the amount of isolation they were experiencing as well. Showing up with the familiar faces of the people they trust most — the providers and the nurses on the team when they come to their medical home — was really, really comforting for families and felt very special between the patients and our team. It was really powerful,” she says.

Patient navigators called families in advance to walk them through the process of the mobile pediatric clinic visits, explaining that the check-ups and vaccinations would take place in the ambulance outside their residence and that providers would be adequately outfitted in personal protection equipment to prevent the spread of COVID-19. The navigators also worked to identify any additional needs that families had, such as for food or diapers, so that pediatric staff could collect and send extra supplies to these homes.

“That is how we think as pediatricians at BMC. Our patients have a lot of needs, and we are always just so aware that we can’t fix everything with a medication. Especially hearing more and more reports of people experiencing increasing financial and emotional distress during the coronavirus outbreak, it makes sense if we are making all this effort to get an ambulance out to our patients’ homes, we drop off some supplies for them at the same time,” says Stulac.

Effective outreach and surprising outcomes

The mobile pediatric clinic, which includes a pediatrician, a nurse, and an ambulance driver, began its first visits in mid-April. The unit visits up to 12 families per day, providing sibling groups with routine care and administering necessary immunizations. Currently, more than half of the department’s in-person visits are delivered via the ambulance, and hundreds of vaccines have been provided.

“In general, it has been extremely well received. It is amazing to be able to be at a patient’s home and give them the service that had been delayed because it was difficult or daunting for them to get out of their house to get to the hospital,” says Stulac.

More than half of the department’s in-person visits are delivered via the ambulance, and hundreds of vaccines have been provided.

Other outcomes have been more surprising for the team. The unit quickly realized that there were health concerns outside the scope of vaccines that needed to be addressed such as acute health issues that required hospitalization, mothers with severe postpartum depression, and even domestic abuse disclosures.

“Basically, we were just trying to meet the needs of our patients at that moment. Whatever it was, if we’re able to do it, we would do it,” says Chase, who underlines how the team is considering moving toward multispecialty care to address the health of both mothers and children. “For example, next week, we are visiting a mother who has a very medically complex child. The mother is on an anticoagulant and hasn’t had blood work done to monitor her condition because it’s difficult to get out of the house with her child’s needs. We are planning to take her blood for labs at the same time we do the pediatric visit.”

Bundling services and removing barriers to care

The BMC Pediatric Clinic is just beginning to re-open after the coronavirus surge. The hallways are still quiet, and it remains unclear how comfortable families will feel about returning to the hospital for routine care. Many BMC families live in multigenerational households, and there is concern about unknowingly transmitting the coronavirus to elderly family members.

The mobile pediatric clinic unit is still running at full capacity, and Costello, noting the many hurdles her patients face to come to the hospital or even access telemedicine, hopes to evolve the model after the pandemic is over.

“We have definitely learned there is a role for this. The areas that stand out for us in primary care pediatrics is postpartum mothers and newborns. It’s just cruel to have to bring a mom back the day after she went home from the hospital with a newborn when she can hardly walk. A lot of our families don’t have cars and have come on public transit with the new baby,” explains Costello, noting this model would also help reduce the high percentage of missed appointments for postpartum mothers.

Many other specialists throughout BMC are also showing interest in using a mobile medical unit to reach their medically fragile patients who have difficulty coming to the hospital. Elderly patients and patients with severe disabilities could all benefit from care at home. Costello notes that the lessons learned by her team over the past few months have been invaluable both in boosting team morale during an extremely stressful time as well as in creating an innovative model with incredible potential.

“You really learn a lot when you see people in their natural environments, and for our professionals who don’t live in the city of Boston, going to places they’ve heard about but never been, like Roxbury, Dorchester, and Mattapan, is very meaningful,” says Costello. “We always ask ourselves, how do we meet our patients and our families where they are, and at BMC, that’s what we do really, really well. But this was truly meeting them where they are at, which is really powerful.”