PrEP for HIV Prevention: Costs and Coverage Aren't the Only Barriers to Care

July 25, 2019

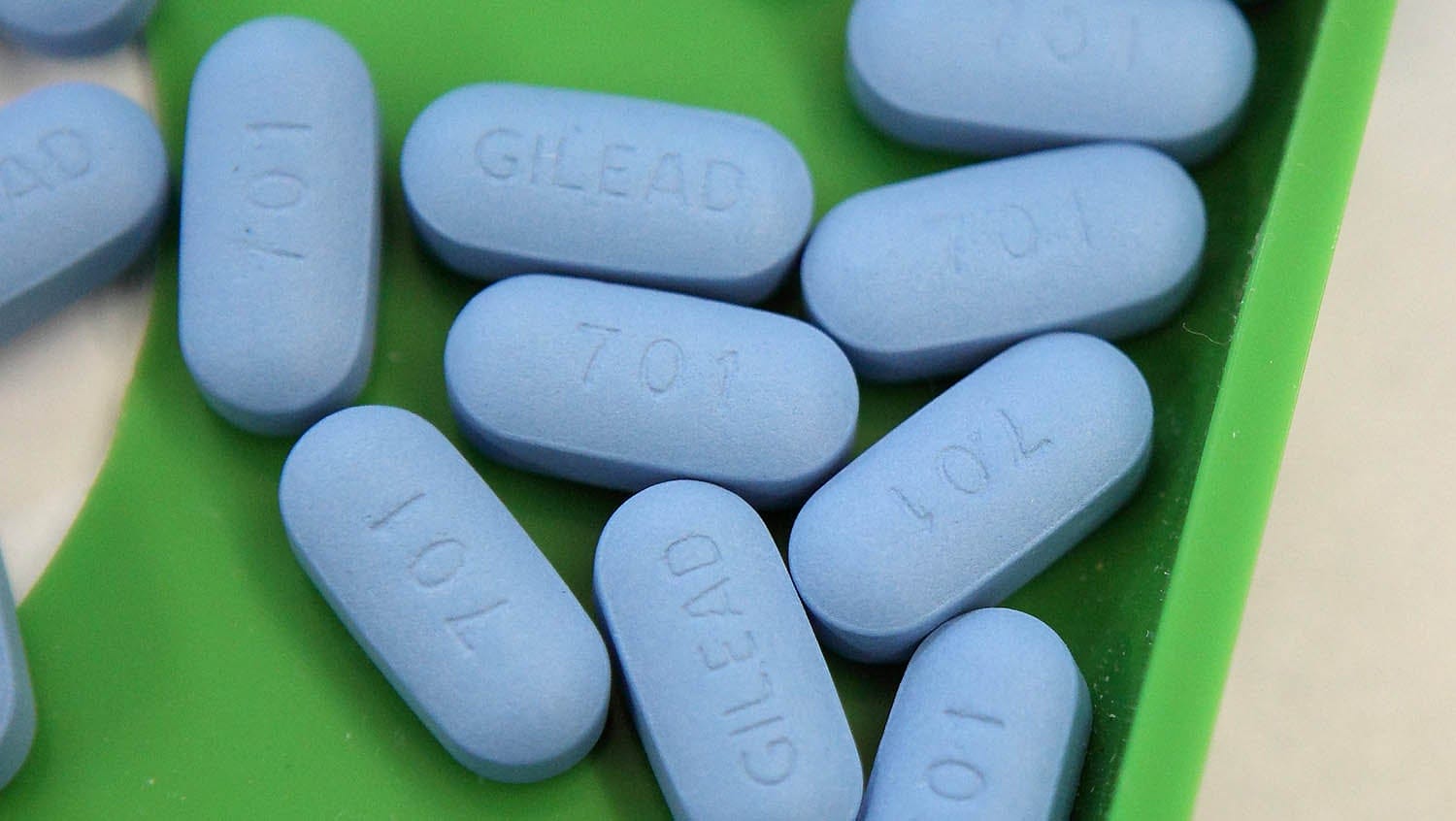

Getty Images

A PrEP navigation model helping providers stay on top of care helps increase PrEP access and adherence.

Providers are not prescribing PrEP (pre-exposure prophylaxis) enough. The drug, also known by the brand name Truvada, can prevent HIV transmission — yet access to the medication still eludes some of the most heavily impacted communities, including black and Latino men who have sex with men (BLMSM), transgender women, and people under the age of 24.

Roughly 1.2 million people in the U.S. are at high risk of acquiring HIV and could benefit from being on PrEP, but fewer than 80,000 people were prescribed the drug, according to 2016 data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). And half of the people receiving the drug were located in just five states, revealing a staggering gap to be filled in prescribing and access.

The gap has largely been attributed to the overwhelming costs of the medication and its related services. Truvada clocks in at $21,000 yearly, and patients often struggle with insurance coverage and applications to drug assistance programs. However, new research suggests costs are just one side of the access problem. According to a survey of internal medicine residents, providers aren’t fully equipped to prescribe PrEP, either.

PrEP is time-intensive for providers. Prescribing the drug requires a commitment to frequent follow-up visits and extensive labs to monitor STIs and liver and kidney function. On top of that, providers need greater training and education in sexual history taking and the psychosocial factors that influence patients’ risk, uptake, and adherence. As a result, patients who manage to get a prescription may fall through the cracks, or some providers may outright refuse to take on the workload at all.

Expecting primary care providers to address PrEP candidacy and monitoring in a typical visit may be unrealistic among all the other medical and psychosocial needs that arise in that time.

“We’re basically expecting providers to do miracles in a 20-minute visit,” says Glory Ruiz, senior manager for the Center for Infectious Diseases and Public Health Programs at Boston Medical Center (BMC).

The key to improved PrEP services, Ruiz attests, is rooted in collaboration between providers and patient navigators.

Provider backup

The Massachusetts Department of Public Health (DPH) has funded many HIV PrEP programs in the state to make PrEP available without barriers to those who are most at risk of HIV. Ruiz oversees a DPH-supported PrEP navigation program at Boston Medical Center that not only helps patients with insurance coverage and costs, but also spends a significant amount of time partnering with providers to decrease demands and encourage prescribing in primary care, which has been shown to be the best place to get PrEP.

Addressing patient barriers, like transportation and insurance problems, takes coordination and time that many providers don’t have.

“We provide a lot of clinician support due to that,” explains Samantha Johnson, program manager of Prevention, Navigation, and Outreach Programs at BMC. “And that support includes different things: education about how to do a sexual risk assessment — because we know that’s one of the areas that needs to be worked on in general in clinical practice, because people aren’t comfortable talking about sex — and also QA work that involves making sure all the right labs were put in, giving the provider support if the right lab wasn’t put in, and really making sure PrEP is being prescribed per protocol.”

The hospital’s PrEP coordinators partner with providers in general internal medicine, family medicine, and OB-GYN to perform sexual risk assessments and conduct quality assurance work. As part of this, the program proactively monitors patients hospital-wide who are positive for certain STIs that could flag a potential candidate for PrEP.

“We’re making sure that we’re saying to providers, ‘Hey, you may have missed this,’” Ruiz says. “Providers like having that safety net of making sure that there is a quality assurance component.”

PrEP monitoring and management

The navigation program, which is informed by the HIV navigation model, makes sure that its work goes beyond candidate identification.

“We’re seeing that getting people started on PrEP is almost the easiest part,” says Samantha Johnson. “It’s really keeping them to that next three-month appointment — that’s where we’ve seen most patients fall off.”

To ensure that patients are properly linked to care, the PrEP coordinator keeps a registry in the hospital’s electronic medical record that pulls anybody who has an active Truvada prescription and is non-HIV positive. Nurses conduct adherence checks while PrEP navigators monitor prescription refills, side effects, and appointment adherence, making sure that patients continue to get HIV testing and other workups in accordance with the PrEP guidelines.

Addressing patient barriers, like transportation and insurance problems, takes coordination and time that many providers don’t have. The PrEP navigation program provides service referral, linkage, and follow-up strategies that assist participants and providers in addressing unmet psychosocial needs, from housing and social support to employment, food security, and intimate partner violence.

Months later, the PrEP navigators are keeping a close eye on creatinine levels in the kidneys and lab scheduling.

Providers can be assured that the PrEP coordinator will know in six months if the patient’s due for their labs, Johnson says, which opens the door for a conversation between the provider and the coordinator about patient outreach and next steps.

“In that way,” adds Ruiz, “We also forge a relationship with the provider, so that not only are we helping them provide their best medical care, but we’re also making sure that we are partnering with them in an overall global preventive medicine approach.”