Transforming Pediatrics: Lessons from 30 Years of Reach Out and Read

November 6, 2019

Getty Images

Barry Zuckerman, the pediatrician who fostered Reach Out and Read from grassroots beginnings, shares insights for innovating in pediatrics.

Reach Out and Read is an international nonprofit, annually delivering more than 7 million developmentally appropriate books to nearly 5 million children during well-child primary care visits in the U.S. alone. The program has seen remarkable bipartisan support, including from former Senator Ted Kennedy and First Ladies Hillary Clinton and Laura Bush. But 30 years ago, the program began as a stack of books in the waiting room of a single pediatric department.

In hindsight, the idea to foster children’s development through reading aloud seems simple. But the concept of introducing literature into pediatric care was ahead of its time when pediatricians Barry Zuckerman and Robert Needlman launched Reach Out and Read at Boston City Hospital, part of what is known today as Boston Medical Center (BMC).

In 1989, there was no guidance for pediatricians on the importance of reading to children —Zuckerman screened for it because he read with his own kids. He discovered that many of the low-income parents he worked with weren’t reading to their children and didn’t have books in the home. Years down the line, their children, though physically healthy, struggled with academic achievement and the emotional tolls of underperformance.

Reach Out and Read places a particular emphasis on addressing social and educational barriers facing children from low-income backgrounds. While 80% of childhood brain growth occurs before age 3, approximately half of children living in poverty in the U.S. begin school unequipped with foundational knowledge and skills. To help reduce inequities between low-income children and their peers, Zuckerman gave families a developmentally appropriate book to take home from each well-visit, a model designed to help families accumulate a small home library by the time the child entered kindergarten.

Since Reach Out and Read’s humble beginnings, much research has emerged supporting what Zuckerman, Needlman, and many early adopters of the program intuitively knew to be true. Reach Out and Read helps children overcome developmental hurdles, helping to narrow socioeconomic achievement gaps. By incorporating books into pediatric care and highlighting the developmental benefits of reading aloud, Reach Out and Read works to foster language ability, social skills, and school readiness.

Zuckerman, now chair emeritus of pediatrics at BMC, has gone on to help build other projects that have also achieved national success, including Medical-Legal Partnership, Health Leads, and Healthy Steps. HealthCity caught up with Zuckerman ahead of Reach Out and Read’s 30th anniversary celebrations, diving into his insights about how a grassroots effort gained international status, his takeaways from the past 30 years of growth, and his philosophy for innovating in pediatrics.

HealthCity: 30 years ago, distributing books in pediatrics was an innovative idea. How did people initially react?

Barry Zuckerman, MD: Well, you know you probably have a good idea when people say, “It’s not what we do.” Science wants science. I had some data, and it wasn’t perfect, but my feeling was, what could be bad? What’s bad about giving books to children? Having books in the home is what well-to-do kids have, so why shouldn’t low-income kids have them, too? It was a principled stand, and I’ll probably make the same today.

When it came to funding, the department of education said, “We’re not going to fund health centers.” And the health people said, “We’re not going to fund books.” By doing the right thing, though, we fell between the cracks of our federal silos. It’s not straddling these ideas. It’s not separating children’s health from their education or welfare. It’s all about children and what the children need. Establishing a unique voice, having pediatricians and doctors talking about children’s early learning and particularly about brain development and opportunity, became important.

HC: At its core, this model seems to center on fostering family self-sufficiency and giving them the tools to take their health into their own hands.

BZ: Absolutely — which I think is really the core of what we have to do as pediatricians. The books are interesting because other advice we give is passive and the parent has to remember doing it. But if there’s a book in a home, the 1- or 2-year-old is going to toddle up to the parent with his hand outstretched, holding the book to elicit the behavior that we want.

“The future of pediatrics is a transformation of how we think about helping parents.”

The bigger picture for Reach Out and Read was certainly to get parents reading to their children. Children are then prepared to enter school ready to learn. But I saw it as more of a catalyst to change pediatrics. The question is, what are the other most important things we can do for the children? I think the future of pediatrics is a transformation of how we think about helping parents. I can give a child an antibiotic, and I can give him an immunization, but they’re the ones raising the children.

HC: With parental involvement being key, how do you broach Reach Out and Read with parents who aren’t confident in their own literacy?

BZ: For 6-month-olds and 12-month-olds, it’s not about reading to them. The point is to get a book with brightly colored pictures of common objects and point and name them. Six-month-olds have joint attention and can look at books with their parents and enjoy it.

I would tell the mother, “It’s not about teaching the child the alphabet or numbers. They will learn to love books if they share books with someone they love. The beginning of the love of learning is the love of books.”

HC: Has the growing availability of mobile devices and e-books changed Reach Out and Read’s approach?

BZ: I’ve heard that some parents are very busy and stressed and putting their 2- or 3-year-olds in bed with an e-book. I can’t imagine anything more antithetical to the kind of relationship-based reading that goes on with Reach Out and Read.

If you watch parents using an iPad, the interaction is just between the child and the iPad. But the key to book reading is not the book; the book is a tool for an emotionally engaged, verbal interaction between a parent and child. That’s what the children learn. It supports their memory. It supports their language development. It supports their social and emotional development. It even supports their fine motor development when they have to turn the pages.

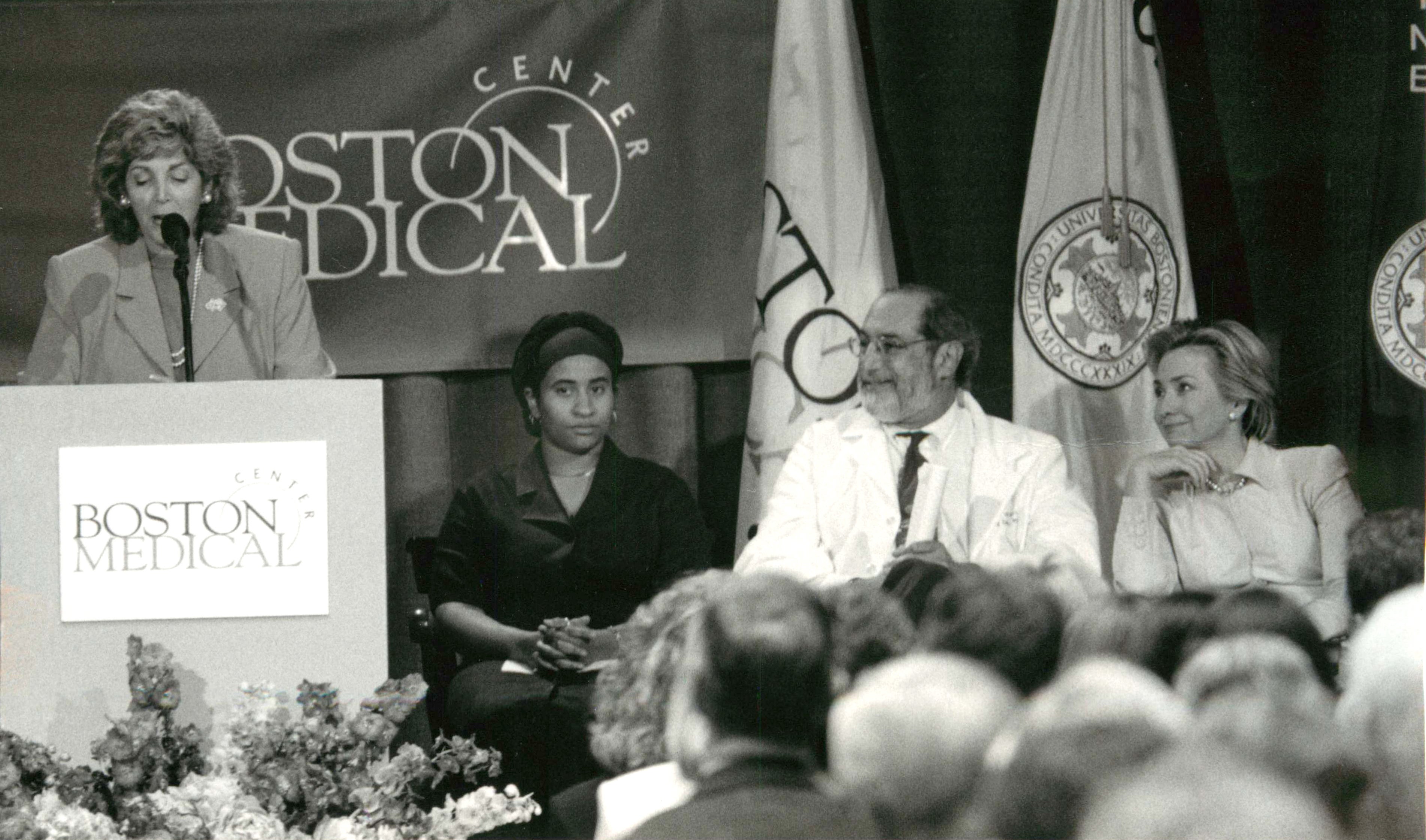

Reach Out and Read co-founder Barry Zuckerman sits next to First Lady Hillary Clinton (right) during the program’s 10th Anniversary Celebrations at Boston Medical Center, where Clinton was keynote speaker. (Photo courtesy of Barry Zuckerman).

Reach Out and Read co-founder Barry Zuckerman sits next to First Lady Hillary Clinton (right) during the program’s 10th Anniversary Celebrations at Boston Medical Center, where Clinton was keynote speaker. (Photo courtesy of Barry Zuckerman).

I think if you were to ask a developer to create a widget that stimulates all aspects of development, the best that he could come up with would be a book being shared by a parent — not the book itself, but with the parent. The parent is key.

HC: Has the extent of Reach Out and Read’s expansion surprised you?

BZ: No — and had there been a line item or money that was coming to us, it would even be bigger. This was totally a groundswell of people wanting to do the right thing for the right reasons. That’s the way it’s spread all over the country — it’d be one pediatrician who wanted to do it, and they did it. And sooner or later they brought in colleagues or took on the whole health center. It really became a very special role for clinician pediatricians who weren’t academics but wanted to make a difference beyond what they had been taught to do. This gave them something that they really valued beyond their clinical roles. They took to this with a passion.

We’re reaching 25% of low-income kids. I wish we could reach all of the low-income kids. This is what I think federal money can do. You’re talking about a couple bucks for the book — next to a healthcare bill, next to kids not entering school, not ready to learn, it’s a good shot.

HC: What are some of the most significant lessons you’ve taken away from your work with Reach Out and Read?

BZ: The lessons were how to implement new innovations. And the lessons I’ve learned helped me implement Medical Legal Partnership, Health Leads, Child Witness to Violence Project. As someone once said to me, “If you want to have a great idea, you need hundreds of ideas.” Everyone knows the ones that are successful, but I can count off another 50 or 60 that never got much beyond the first discussion.

“That’s the process of lean startup — you try something on a small scale without a big financial or labor investment. And if you get some positive feedback, you do a little more.”

But that’s the process of lean startup — you try something on a small scale without a big financial or labor investment. And if you get some positive feedback, you do a little more and you keep building that way. Here’s the way I think about it: When some people see things not going well, they complain about it. Others’ heads work more like, “What can we do to make changes?” The kids weren’t doing well in school, parents weren’t reading. I could have said, “You should read to your child.” But instead I gave them a book, and that seemed to happen.

People could say, “Why pediatrics?” I can say, “Why not? Who else?” We all have a role to play in helping families with young kids.