Progress Against the Opioid Epidemic Is Not Reaching Black Americans

February 1, 2021

Getty Images

Treatment and harm reduction approaches for opioid use disorder have failed to effectively meet the needs of people of color, experts say.

After witnessing skyrocketing rates of overdoses, the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services declared the opioid epidemic a public health emergency in 2017. Since then, and through 2019, opioid overdose deaths have decreased, according to a 2020 CDC report. But this achievement doesn’t mean that interventions and treatment for opioid use disorder (OUD) are entirely successful — far from it, and particularly not in Black communities.

New data from the Massachusetts Department of Public Health tracks opioid-related overdose deaths in the state by race, ethnicity, and gender from 2014 to 2019. The absolute number of deaths is higher among whites than among Hispanic or Black Americans, though all groups were on an upward trajectory until 2016.

Since 2016, however, the story has changed. While white fatalities have decreased through 2019, opioid overdose deaths among Black Americans — particularly Black men — are accelerating.

Overall U.S. data follows similar patterns. From 2011 to 2016, Black Americans had the highest increase in synthetic opioid-involved overdose death rates compared to all populations. And while from 2017 to 2018, overall opioid-involved overdose fatalities decreased by 4.1%, rates among Black and Hispanic people actually increased.

Reductions in fatalities are disproportionally accruing to whites, “whereas things seemingly have worsened in Hispanic and Black non-Hispanic groups,” explains Marc LaRochelle, MD, a primary care physician specializing in addiction medicine at Boston Medical Center. “In the last three years, it looks like the brakes had been put on for white population, but the other groups are still going up.”

The new data shows how our current interventions for OUD, and substance use disorder (SUD) overall, aren’t working well enough for everyone. When it comes to opioid overdose deaths, LaRochelle says, “It’s not that the Black and Hispanic groups are seeing disproportionate increases; it’s that they haven’t seen the advantage from the advances and changes that have been made.”

Fourth wave of the opioid epidemic

U.S. experts mark the start of the current opioid epidemic with the rise of prescription opioid analgesic use for nonmedical reasons, particularly Oxycontin, in the 1990s. About 2010, the second wave of the crisis brought heroin to the forefront. But in 2013, the third wave of the epidemic posted a steep rise in synthetic opioid overdose deaths, due mainly to fentanyl.

According to the CDC, the number of overdose deaths that included fentanyl more than doubled every year from 2013 until 2016 — which LaRochelle notes mirrors the upward trajectory in the overdose data across race and ethnicity groups in Massachusetts. “Fentanyl hit everyone all at the same time,” he says.

Synthetic opioids are still the leading cause of drug overdose deaths in the country as the U.S. is grappling with the fourth wave of the epidemic. This wave is characterized by an increase in polysubstance use — combining opioids with other drugs such as benzodiazepines, methamphetamine, and notably, cocaine.

Some of this polysubstance use involving opioids is inadvertent, however, as reports are showing that fentanyl is finding its way into the cocaine supply.

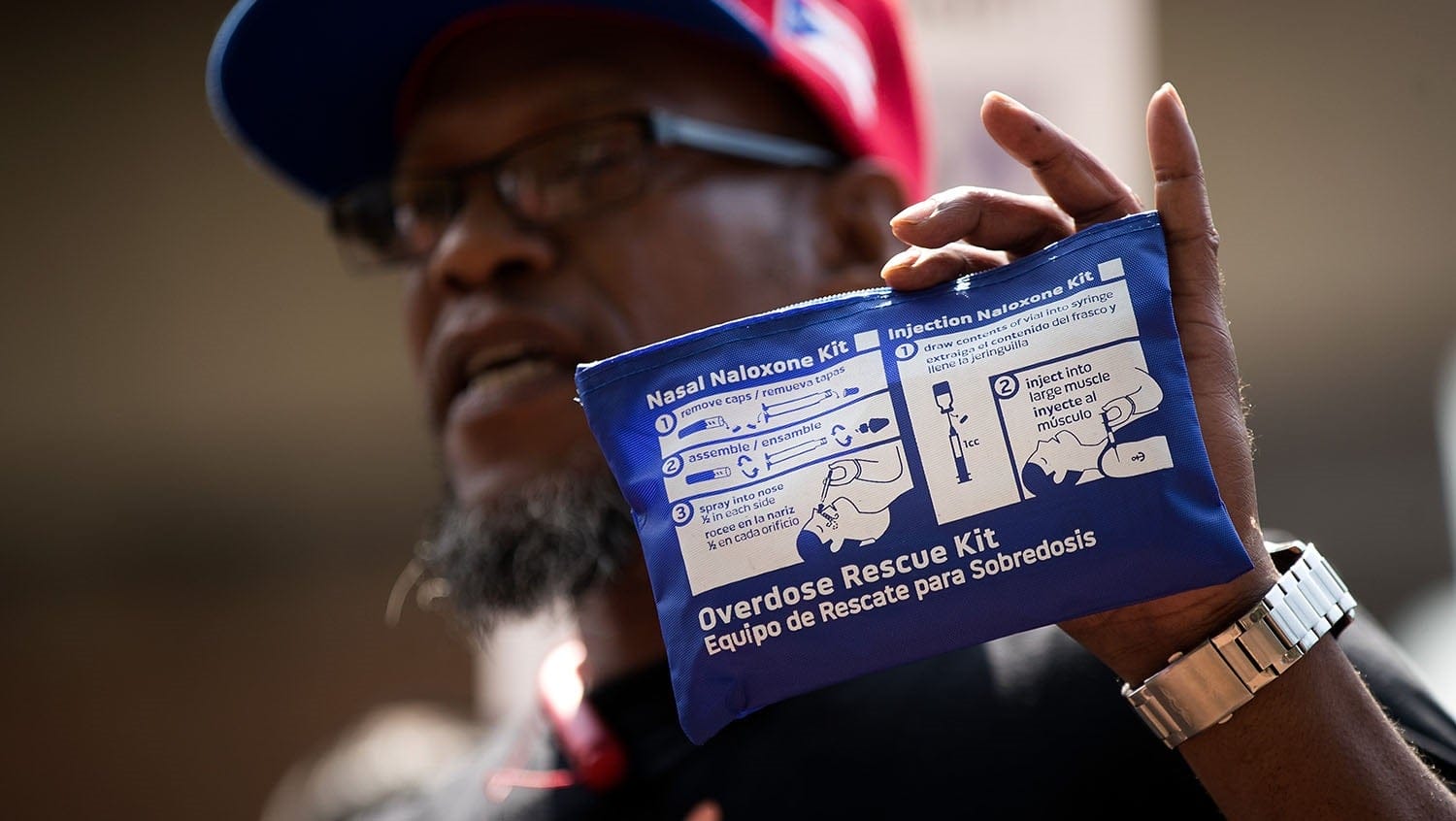

Overdose deaths involving cocaine have nearly tripled in the U.S. from 2013 to 2018. That’s especially alarming for Black people for whom cocaine is more often the substance of choice if cocaine were unknowingly mixed with opioids, explains LaRochelle: “Now you’ve got an opioid-naïve individual who’s intending to use cocaine that gets fentanyl in there too, and it’s a recipe for an overdose.” Opioid-naïve individuals, he notes, are also less likely to carry naloxone, an opioid antagonist that works as an antidote to reverse an overdose.

Why hasn’t addiction treatment effectively reached Black people?

While there is a long history of racism in responses to drug use by Black versus white Americans, including the war on drugs which disproportionately targeted Black people with SUD — the truth remains that even efforts framed as treatment and prevention rather than punishment fall short. A significant part of that issue is the perception of the opioid epidemic as a white crisis: in raw numbers, the epidemic has affected more white people and — before the onset of fentanyl — at higher rates.

“Some people look at the data and note that our response to treating and managing opioid use disorder in a harm reduction approach took off at the same time where this crisis started to affect a different group of folks,” says LaRochelle. And that’s a problem, according to Keturah James, law clerk and Yale Law School graduate, and Ayana Jordan, MD, professor of addiction psychiatry at Yale, in their paper “The Opioid Crisis in Black Communities.”

“The issue is not that white people aren’t affected by the crisis — they are, and in record numbers — but rather that Black Americans, often left out of the greater discussion, have been and continue to be adversely affected by the same epidemic,” they write.

Moving treatment forward with targeted approaches

LaRochelle acknowledges that the effect of the epidemic on the Black community is complicated: “I don’t think there’s a simple thread you can pull on this and tell the whole story,” he says. But there are areas to address.

Any new advances and changes must incorporate targeted approaches for nonwhite Americans with SUD — whether that’s opioid, cocaine, or polysubstance use — because, as LaRochelle says, “Whatever we’ve done to get harm reduction treatment and preventive-type resources to patients and people who use drugs who are white has not reached other at-risk populations equally.”

When it comes to access, structural racism built into healthcare and the SUD treatment system has been a longstanding concern. Jones and Jordan write that any approach must consider stigma and trauma, particularly Black people’s interaction with the criminal justice system related to substance use.

“Explicitly framing treatment of a substance use disorder as a health problem, rather than a racially bifurcated law enforcement issue, signals to Black people that clinicians and health advocates are aware of the disproportionate legal repercussions that people of color face, and will take this into consideration when helping them,” they write.

LaRochelle also calls out the disparities in pharmacotherapy, particularly the difference between use of buprenorphine and methadone, two FDA-approved medications to treat OUD. The former tends to be more accessible in medical settings to which Black patients are less likely to have access. Because methadone carries higher chance of overdose, treatment requires daily appointments for monitoring — as opposed to take-home pills or a long-lasting injection of buprenorphine — creating substantial barriers to care. Not only that, but zoning restrictions for opioid treatment programs, where these appointments take place, make them more difficult to find and access.

Advances and successes in the opioid epidemic thus far haven’t just disproportionately accrued to white people — LaRochelle cautions that it’s leaving disparities that can grow even bigger if not corrected.

“Unless you’re intentional in how you’re measuring, examining, and approaching these problems, it’s quite possible that your healthcare solutions are going to widen disparities,” he says.