Opioid Stewardship Alone Misses Opportunities to Predict and Prevent Overdose Death: A Roadmap for Intervention

September 18, 2019

Getty Images

To tackle the overdose epidemic, focusing on opioid prescriptions alone is not enough. New research shows that we’re missing opportunities to save thousands of lives.

Every day, more than a hundred Americans die from opioid overdoses — and every day, we miss critical opportunities to save the victims of tomorrow.

For years, we’ve approached this epidemic by focusing on prescription painkillers. As a society, we’ve tightened regulations in an attempt to stem the flow of opioids, kept an ever-watchful eye on patients, and spread awareness about the safe usage and disposal of these medications. And for good reason; opioid stewardship is an important part of the solution.

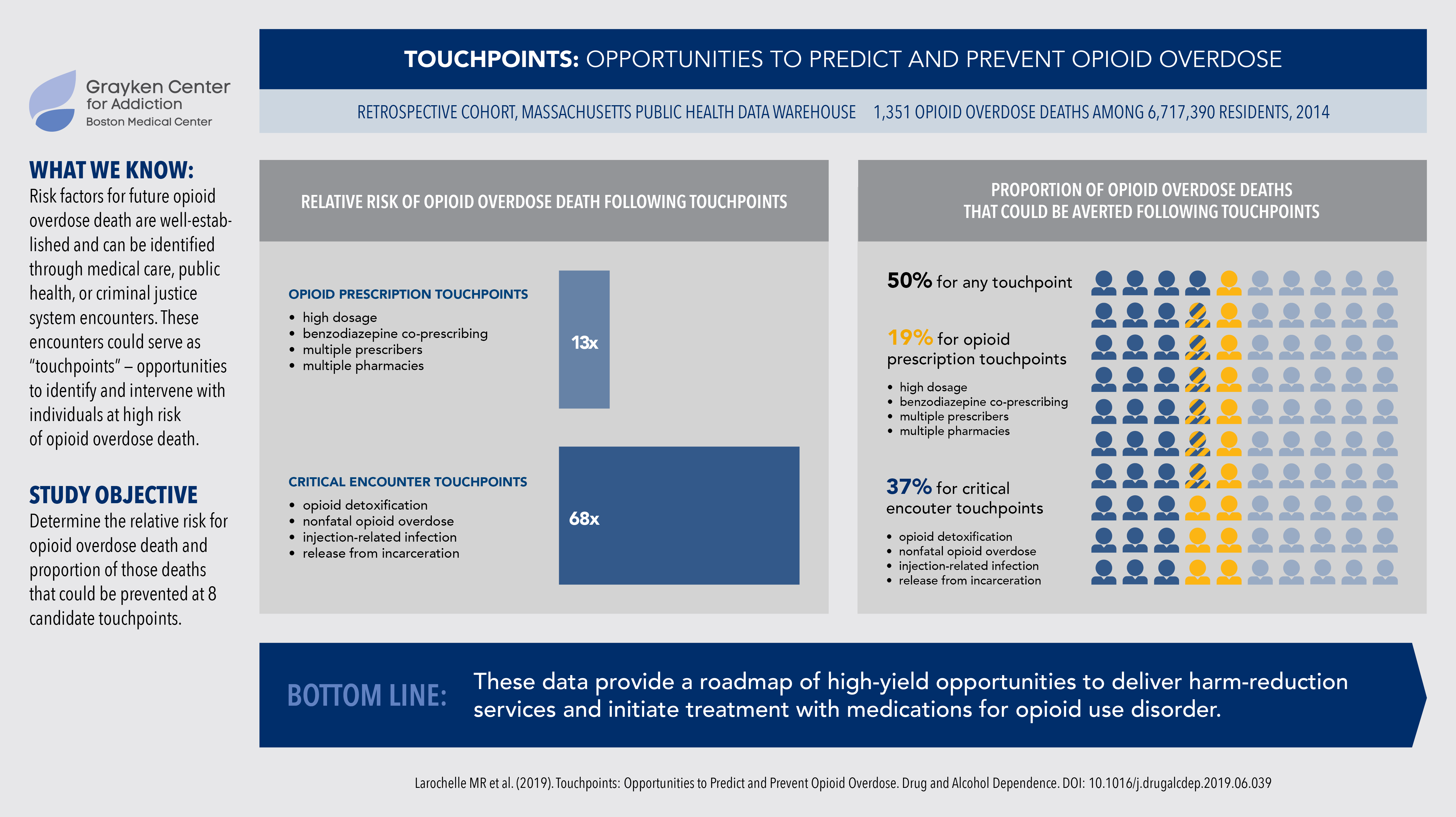

But how many overdose deaths are actually attributable to prescriptions — and where might we find other opportunities for the delivery of lifesaving interventions? It’s true that people are more likely to die from an overdose if they are prescribed a high dose of opioids, combine opioids with sedatives, or obtain prescriptions from multiple prescribers or multiple pharmacies. Still, we recently found that four other critical encounter touchpoints are associated with a staggering 68-fold increase in risk of death — that’s five times the risk associated with high-risk prescribing. Those touchpoints are detoxing from opioids, experiencing a prior nonfatal opioid overdose, sustaining an injection-related complication, or being released from incarceration.

These touchpoints are missed opportunities to save lives, and as many as half of opioid-related deaths could have been prevented through delivering interventions at these encounters. To reduce opioid-related harms, the research shows we have to think bigger than opioid stewardship alone.

Treating opioid use disorder at the critical touchpoints

Opioid use disorder (OUD) has effective, evidence-based treatments, but they’re largely underused even in opportunities where they could have the greatest life-saving impact. For example, every high-risk individual should be offered naloxone and overdose education, interventions that could save their life or the life of someone they know who also uses drugs, regardless of their readiness to enter treatment. Research also consistently demonstrates that medications for OUD, such as buprenorphine and methadone, are powerful tools in the battle against the opioid epidemic. The longer people stay on these medications, the lower their chance of relapse and overdose. While most often viewed as outpatient treatment, research has shown initiating these medications in acute care settings is feasible.

Because critical encounter touchpoints are associated with such a massive increase in opioid-related deaths, providing care during these particular experiences could save thousands of lives every year. Let’s take a look at what this care could entail at each high-risk encounter.

Opioid detoxification

The term “detoxification” is problematic in itself. Instead of detoxing patients, we could use this touchpoint as an opportunity for treatment initiation. Many patients already indicate interest in starting medication for OUD after detox.

Nonfatal opioid overdose

After an overdose victim has fought for their life in an ambulance or hospital, the standard care is to stabilize them, release them, and perhaps provide a referral to treatment. But instead of simply referring them, why can’t we seize this experience as a chance to begin treatment with medications for OUD?

Injection-related complications

When patients with OUD seek care for complications related to their drug use, we tend to treat the infection, release them, and perhaps provide a referral to care. But this face-to-face encounter, too, is a missed opportunity to provide harm reduction services and treatment for the use disorder that underlies their presenting condition.

Release from prison

Many have been concerned about allowing methadone and buprenorphine in prisons, but facilities that allow it are demonstrating that it’s feasible. We know that the two-week period after people are released from prison is particularly high-risk. These people have the best chance of staying alive if they’ve already started on treatment when they leave.

Paramount to all of the above, we should ensure individuals who use drugs feel welcome in our emergency rooms and healthcare systems. In a culture where addiction issues are often still surrounded by stigma and shame, even institutionally, this trust may take a while to build. Until then, alternative pathways are more important than ever: places like the Boston Medical Center (BMC) Faster Paths urgent care center, BMC’s Office Based Addiction Treatment, and Massachusetts General Hospital’s Bridge Clinic.

Ending prescriptions won’t end the epidemic

The majority of people with OUD still start by using prescription drugs. We know that we can reduce addiction rates and save lives by avoiding long-term opioid prescriptions for new patients whenever possible, but these substances appear to be playing a smaller role in the overdose epidemic compared to past years. As prescription opioids become harder and harder to obtain, users’ first opioid exposure may be shifting: A recent study found that 9% of people with OUD started by using heroin or fentanyl in 2005. By 2015, that number had soared to 32%.

Furthermore, many long-term users of prescription opioids may turn to these riskier substances if their doctors suddenly cut their prescriptions. Millions of Americans were prescribed opioids for pain before providers fully understood the risks, and now, many policies and programs advocate tapering these patients from their medications no matter what. However, emerging evidence from the CDC, the FDA, and other studies suggests that abrupt, inappropriate tapers could actually increase harm.

In our research, we examined whether the time elapsed from a touchpoint affected rates of overdose death. A person actively receiving high-dose opioids, we found, was 14 times more likely to die from an overdose. Meanwhile, people who had received high dosages two to three years earlier but no longer had that prescription were still about 14 times more likely to die from an opioid overdose. In other words, when we take away the prescription, the risk of a fatal opioid overdose remains high.

There are no easy answers, but in light of that data, we know that we cannot simply focus on stopping prescriptions. These high-dose patients, too, must be guided by their clinicians with thoughtfulness and empathy. Many may benefit from careful tapering of their drugs. Others may be best served by continuing to receive opioid prescriptions. And still others may benefit from medications for OUD, such as methadone and buprenorphine.

For all patients affected by the opioid epidemic, treatment and recovery are individual. A strategy that works for one person may not work for another, and we still need more data to determine the most successful courses of action.

But in the end, nobody needs to die from using opioids. In a situation that’s rife with pain, struggle, and death, we have so many reasons to be hopeful. We have treatments that work. Let’s seize the opportunities to use them.