Why Isn't the Opioid Epidemic Getting Any Better?

November 17, 2020

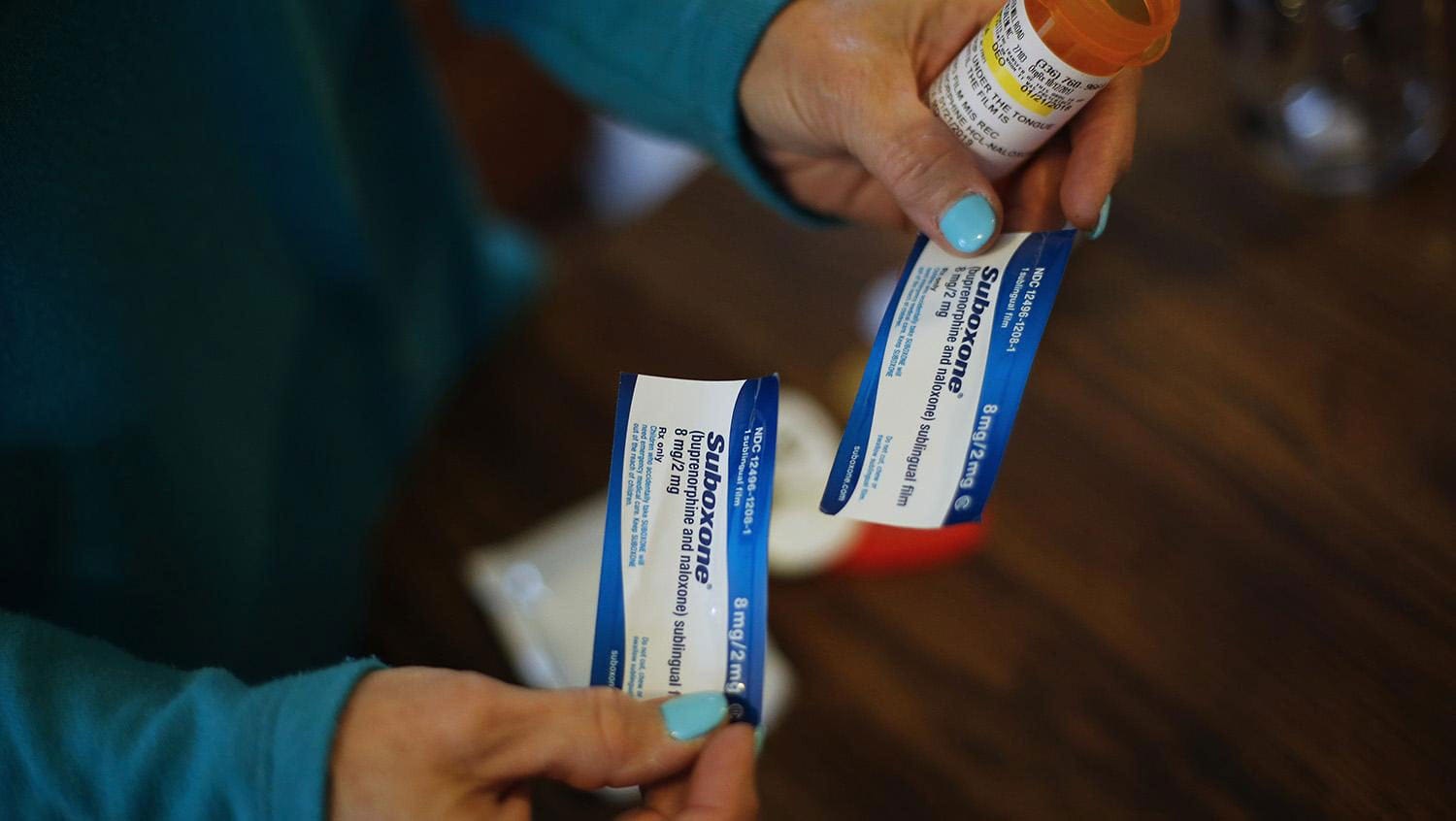

Getty Images

Despite efforts to combat the opioid epidemic over the past decades, the data shows that death rates have not significantly improved — calling for a paradigm shift in how care is delivered.

The number of drug overdose deaths in 2019 climbed 4.6% compared to 2018, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, with a total of 70,980 deaths. More than 50,000 of those deaths involved opioids. Despite the attention and resources put forth to combat the opioid epidemic over the past several decades, the data shows that death rates have not significantly improved.

HealthCity recently asked Alex Walley, MD, addiction medicine expert and physician in general internal medicine at Boston Medical Center, why. His answer points to real and perceived barriers to treatment access and the need for a paradigm shift in how care is delivered.

Alex Walley, MD

“There is a wealth of research data showing that people with opioid use disorder who take buprenorphine or methadone are less likely to die. It doesn’t get clearer than that. However, the underlying issue is access. How can we help our patients access these life-saving treatments? I think that answer is centered around our approach.

Instead of making patients come to us, we should be doing more to get treatment to patients, meeting them where they are at. To decrease opioid overdose deaths, we need to remove barriers to treatment access and help people stay safe through harm reduction.

The need for patient-centered care is particularly the case for high-risk individuals, including those leaving incarceration or being discharged from the hospital or a detox facility: A recent study showed that upon leaving a detox facility, only 30% of patients went on to an outpatient treatment program; and the retention rates for those who are engaged in care are low.

One potential solution that combines treatment and harm reduction is expanding the scope of syringe service programs to include access to medications for opioid use disorder. Pairing medication with harm reduction approaches in places where patients already go for services represents a unique opportunity to increase engagement in evidence-based treatment approaches.

Another approach includes collaborations among health care organizations, public safety, and public health organizations at the local level to engage individuals at risk of overdose and their families. If a person leaving incarceration has been started or continued on medication for their opioid use disorder while incarcerated, for example, it is key that they engage with a provider within their community so they will continue receiving treatment and thus have a lower risk of overdose. In addition to facilitating access to treatment, we should also equip people with the tools to keep themselves safe if they do use opioids, like overdose prevention education and naloxone rescue kits.

One key focus in access improvement must be on removing stigma from the equation. If a person with a substance use disorder doesn’t seek treatment because they feel ashamed or they’ve been mistreated during previous encounters with the healthcare system, that is one less person we have a chance to help. We must push for the rights of our patients and continue public health and education messages aimed at calling substance use disorder what it is — a disease.

As a doctor, it is my responsibility to make sure that each and every patient has access to the treatment and services that would most benefit their needs. We can’t rely on the traditional model where we expect patients to come to us. We need to center our approaches around the patient, delivering care and bringing services to places in the community where our patients live.

Otherwise, we will not be successful in reducing overdose deaths.”