Why the Way We Talk About Mpox Matters

June 21, 2022

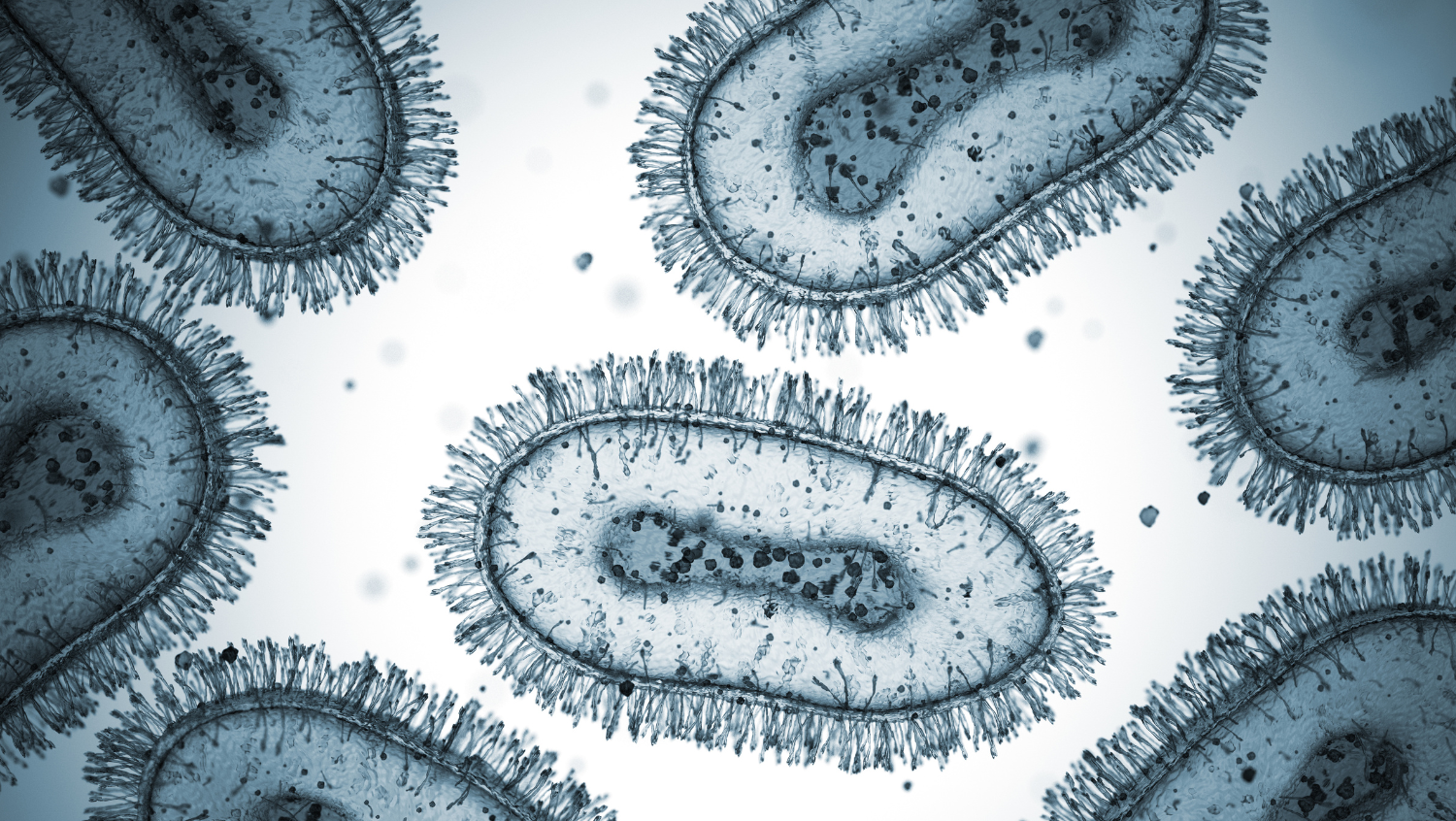

BlackJack3D, Getty Images

Addressing biases in mpox, previously known as monkeypox, coverage is imperative in reducing stigma and, ultimately, providing treatment.

In May 2022, several countries–including the United States–started seeing reports of mpox, the first United States case being in Massachusetts after the patient returned from travel in Canada. The reports of the outbreak, of course, come in tandem with the current COVID-19 pandemic, leaving space for much misinformation, fear-mongering, and, unfortunately, biases based on sexual orientation and ethnicity.

What is the mpox virus?

Mpox is a member of a family of viruses that is closely related to smallpox, and it leads to an illness that can have an initial phase with fever, muscle aches, swollen lymph nodes, and headaches, then explodes in lesions that start out as little red bumps which progress to pustules or pox-like lesions. Given that the disease shares a lineage with smallpox, the smallpox vaccine is incredibly effective against mpox. Because the United States has long feared that smallpox would be used as an agent of bioterrorism, we have a healthy stockpile.

Why was it called ‘monkeypox’ (now called mpox)?

The term “monkeypox” itself is actually somewhat of a misnomer since it can also be carried by several different types of rodents. Monkeypox was given its name because it was identified in a lab studying infection in monkeys in 1958.

We don’t yet know how many different animal species are carriers of the disease. As of now, we know that non-human primates are and that certain kinds of rodents can be. Now, we use the less stigmatizing and more accurate term “mpox.”

Human origins of mpox

The first human case of mpox was discovered in 1972 in Central West Africa. Ever since, the disease has been identified in the Democratic Republican of the Congo (DRC) and Nigeria, but cases have also been seen in recent years in several other countries such as Guinea, Cameroon, and the Republic of Congo. It’s been gradually increasing and part of the reason for this is that younger people who have not been vaccinated against smallpox are increasingly becoming infected as they do not benefit from the long-term protection that smallpox vaccination appears to confer for mpox.

Globally, there have sort of been two strains identified to date and there’s now conjecture about a third strain. Of the two strains, one strain, more commonly seen in the DRC, can cause more severe infection and, in countries without access to modern medicine, can lead to up to a 10% case fatality rate. Though in countries with access to modern medicine, the case fatality rate could be lower. The other strain, usually found in West African countries like Nigeria, causes milder illness and has thus far been associated with a death rate of less than 1% and, probably with optimal care in the United States, should be close to zero.

Though mpox is rare outside of the African continent, this is not the only time there has been a mpox outbreak in the United States. In 2003, there was a moderate-sized outbreak, associated with imported rodents from Western Africa, which cross-infected prairie dogs in pet shops and led to a focal outbreak in the Central West of the United States. Though this disease is endemic to parts of Africa, it is crucial that this is not framed as an “African” disease, especially since a large number of cases in this current global outbreak have no clear link to Africa.

Comparing this outbreak to others

Given the current COVID-19 pandemic, people are nervous about how easily transmissible this new virus is and, as a result, it is getting a bit of media coverage, some of which is very stigmatizing, not only to individuals from African countries, but to men who have sex with men.

This ongoing outbreak is an unusual one because a lot of it has been transmitted through close sexual contact and we’ve never seen this mode of transmission before. Compared to SARS-CoV-2, the mpox virus is much less transmissible. From what we’re seeing in this outbreak and what has been seen in Central Africa over the decades is, you need to have fairly intimate skin to skin contact with someone to become infected.

While many of the current cases are more prevalent among men who have sex with men, there is no research at this time to suggest that this disease is solely linked to gay and bisexual men. Therefore, it should not be framed as such. There’s a risk for everybody who has close, sustained, skin to skin contact with an infected person and there may also be a small risk for transmission via respiratory secretions but a much lower risk than SARS-CoV-2.

How to combat mpox

Right now, all sexually active populations should be really careful and use caution, including having protected sex, especially when engaging in non-monogamous sex.

For communities where the disease has spread more widely, it would be harmful for health care providers to not do individualized, thoughtful and compassionate outreach and education about the disease to increase awareness.

Collectively as public health experts, we need to work on strategies to get messages out to these populations and that requires a multifaceted approach. First, working with these communities, trying to talk to them and figuring out what their information sources are is crucial. Then we have to use those information sources and craft messages in a manner that isn’t stigmatizing or fear-mongering, but reduces harm and controls infection.

In the case of mpox, we’re so much better prepared than we were for COVID-19 and other outbreaks. We have drugs that work against the virus and we have two vaccines that can help prevent it, and we’re already starting to do ring vaccination (administering vaccines to close contacts of those infected) to try and protect people that have been exposed to minimize the spread. Given this activated response, the current outbreak will likely not go very far. However, it’s another test of our system that has recently been weakened and strengthened by our collective response to COVID-19.

The crucial point I want to stress is that with any new outbreak of an infectious disease, we need to have good surveillance systems in place. We need to identify outbreaks early, do contact tracing and isolation of infected individuals, and better understand how the disease is transmitted, and then we might need to step in with measures to prevent transmission—masking, social distancing, safe sex, improved hand hygiene or any combination of those interventions. Of course, utilizing existing or developing vaccines and medications to treat the illness are incredibly important aspects of the response. And, too, we must work with populations who are uniquely vulnerable to disease while taking care not to stigmatize an entire group of people.